An enormous open pit gold mine—now abandoned—is poisoning water flowing into the Fort Belknap Reservation of Montana. Aaniiih Nakoda College, with support from the National Science Foundation, is establishing a research and policy center to monitor the impact and promote sound water policy.

By Paul Boyer

For as long as they lived in what is now northern Montana, the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine people depended on the Milk River. Flowing out of the Rocky Mountains to the west, it provided water for the arid eastern plains, sustaining the grasslands, wildlife, and people who lived along its cottonwood-shaded banks.

In the late nineteenth century, however, European settlers began arriving in the region, lured by promoters who promised rich soil and ample water for agriculture. The Gros Ventre and Assiniboine, now living within the defined boundaries of the Fort Belknap Reservation, watched the Milk River shrink as homesteaders upstream began diverting water to irrigate their fields.

The federal government, siding with the tribe, issued an injunction against the homesteaders. When the setters appealed, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Ruling in favor of the tribe, the court said all federally recognized reservations had an inherent right to water—the court called it a “reserved” right. Even when treaties did not specifically mention water, the right was implied. Now known as the Winters Doctrine, it was a major victory for the Fort Belknap Reservation. It assured access to water from the Milk River and other sources for residents and their emerging agricultural economy.

A century after that landmark court ruling, however, the future of Fort Belknap’s water is once again in question. “Water is becoming more and more scarce,” said Tribal Chairman Andrew Werk Jr. The problem is not simply increased demand. According to hydrologists, the supply of fresh water in the west is actually decreasing due to a warming global climate. For the tribe, the challenge is not simply to protect water rights, but to also wisely use the water they have.

Additionally, many residents are deeply concerned about contamination of existing water sources caused by run-off from an enormous, and now abandoned, open pit gold mine just outside the reservation. For several decades, tons of rock were dug out of mountain tops in the search for gold. When the gold played out, the company went bankrupt, but the environmental damage was already done. The state spends $2 million annually to treat run-off, but several reservation creeks are now badly poisoned.

In the past, tribal members felt they had little power to protect their water rights and waterways. The federal government was an ally a century ago only because it wanted tribal members to become farmers, which was viewed as a path to assimilation; subsequent court rulings have weakened the Winters Doctrine. Meanwhile, the state of Montana often sided with mining companies, allowing for the expansion of gold extraction against opposition from the tribe while downplaying environmental impacts.

All this has left a legacy of suspicion and resentment. “According to the World Health Organization, water is a fundamental human right,” observed Bill Bell, a tribal member and biologist. “But in a capitalist society, that’s not true,” he said. “Water flows to money.” For many tribes, water policy was effectively determined by outside interests.

Aaniiih Nakoda College, located on the Fort Belknap Reservation, is now working to shift the balance of power. A five-year $3.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation is supporting development of the Nicʔ-Mní Center, an interdisciplinary research and policy center that will study the reservation’s water needs, monitor the health of local streams, and develop ways to minimize water use in agriculture. Based at the college, the center will help the tribe formulate its own water policies, rather than relying on state and federal agencies.

The goal, according to Scott Friskics, the college’s director of sponsored programs, is to provide community members with “knowledge, skills, experiences, and credentials”—all the tools required to protect water rights and care for the tribe’s water resources. Funded last fall, the center sponsored its first annual Water Forum this past spring, introducing the community to the new initiative and providing an overview of the issues it will examine. By this fall, the center will begin working full time on its research and data collection.

One of the first priorities for the center’s research staff is to expand ongoing monitoring of several streams flowing out of the Little Rocky Mountains on the southern edge of the reservation, particularly those that originate around the site of the former Landusky-Zortman gold mine. Originally part of the reservation, the region—a 40,000 acre “notch” of land—was purchased by the federal government in 1896 after gold was discovered, for which the tribe was paid $360,000.

At first, miners tunneled underground with picks and shovels. In the 1970s, however, the operation shifted to strip mining. Mountain tops were leveled and vast cavities created. Ore was hauled out by trucks, crushed, and then sprayed with cyanide to extract gold while tailings were dumped in large and growing piles around the mine site.

Cyanide allowed the mining company—the Canadian-owned Pagasus Corporation—to profitably extract tiny particles of gold. However, vast amounts of ore had to be removed for the few ounces of gold it contained. The federal Bureau of Land Management approved nine expansions of mining operations, said Bill Bell, “without once asking for a full-scale environmental impact statement.” At one point, Landusky-Zortman was the world’s largest cyanide heap leach mine. “I was born and raised here,” he said. “I still have a hard time grasping the situation.”

When mining began in the nineteenth century federal officials reassured the tribe that their water rights would not be impaired. By late 1990s, however, reservation residents watched water from several streams turn red from mine run-off. The culprit was acid mine drainage, which lowered the water’s pH, making streams inhospitable to fish and insects. The waterways also contained arsenic, cyanide, lead, and other metals at levels considered unsafe for humans.

The mine was declared a CERCLA (Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act) site in 2004 and is now closed to the public. As part of the Nicʔ-Mní Center’s Water Forum last spring, however, a tour was arranged with state approval. On a cold April morning, a group of college faculty, staff, and community members traveled in a small caravan of vans and pickup trucks to the mine, which many tribal members have rarely, if ever, seen, despite its proximity to the reservation.

Located deep in the Little Rocky Mountains, it is accessible from the reservation by a single dirt road that first passes through a scenic canyon and the tribe’s meadowed pow wow grounds before climbing into a forest of lodgepole pines. At the moment when it’s useful to engage the four-wheel drive and easy to believe that there is nothing left but wilderness, the road rounds a corner and the mine appears.

It’s not possible to see the entire operation from a single vantage point, but this partial view is startling nonetheless—a deep gash across a mountain face, dropping into an enormous trough. Parts of the mine have been “reclaimed” and grasses are now softening the excavated hillsides, but standing on the edge of the enormous Landusky mine pit, Wayne Jepson, a hydrologist with the state’s Department of Environmental Quality, explained that the lasting damage is happening underground.

Rock exposed by the mining process held trace amounts of gold, but it also contained large amounts of pyrite, commonly known as “fool’s gold.” Buried deep underground, pyrite is harmless, but when uncovered and exposed to the elements it breaks down to iron and sulfuric acid. This sulfuric acid “makes a very acidic water,” Jepson said, “and that water dissolves other metals out of the rock, like cadmium, and zinc, and arsenic.”

This water, draining out of the mine site from leach pads and excavations, soon reaches streams that flow out the mountains. Several—Swift Gulch, South Big Horn, and King Creeks—flow into the Fort Belknap Reservation. By the late 1990s the water in all three were turning red from the iron. While streams were visibly impacted by the run-off, inconsistent testing by federal and state agencies made it hard to document the full environmental impact. To help fill the gap in research, Aaniiih Nakoda College established a water lab in the 1990s to track the health of streams flowing onto the reservation. Data collected conclusively showed that run-off from the mine had killed off nearly all water life. Fish were gone; so, too, were the insects and larvae that are normally found in healthy waterways.

The mine is now managed by the state of Montana, which has incrementally constructed an assortment of containment ponds, treatment plants, and filtering systems worthy of Rube Goldberg. Jepson made it clear that much of the state’s work is the result of trial and error. Water moves, often in unpredictable ways, he said, and fixing one problem sometimes creates another. One set of tanks built to process water draining from a leach pad was emitting a strong odor of sulfur; no one knew why. At the top of the hill, water being pumped through another tank filled with gypsum was gurgling into an open pond, thick and scummy. Jepson suggested that we not get too close.

Elsewhere, the state’s work is making a difference. A few miles away, a newly constructed treatment plant now collects and cleans all of the water flowing into Swift Gulch. It’s essentially a small-scale municipal water system; the stream is diverted into a pipe and passed through several tanks where sediment is collected and lime added to raise the pH.

Still, none of this actually fixes the underlying problem. The state is plugging holes and cleaning some of the water, but the corrosive chemical reactions unleashed by the strip mine cannot be stopped. All effort is simply focused on containment. Even the sludge filtered from Swift Gulch is simply hauled back to the leach pad where, in theory, it will eventually wash back down. “That’s job security,” someone observed during the tour.

In this context, success is defined as the continuous operation of collection and filtration systems, twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year– “in perpetuity,” said Bill Bell, speaking at the Water Forum. “Perpetuity. That means forever, people,” he said.

That also means that the work of monitoring must also be sustained, which is one reason why Aaniiih Nakoda College sought funding from the National Science Foundation for development of the Nicʔ-Mní Center. “Nicʔ” means “water” or, more generally, “fluid.” It is also a reminder that stewardship of the land is a longstanding cultural value for the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine people.

“We were the original ecologists,” said Terry Brockie, a tribal member who worked for the U.S. Forest Service. A trained biologist, he is now CEO of Island Mountain Development Group, a for-profit economic development group chartered by the tribe. Speaking at the Water Forum, he said Native peoples did not strive to control or dominate nature. The Christian notion of “dominion” he said, “leads to property rights, ownership, profit” and—ultimately—waste and environmental damage. The Native worldview, in contrast, values sharing and sees humans as part of, not separate from, the environment.

Caring for water was a “central tenet” of this worldview. “If you don’t have water, you have to pack up you camp and go someplace else,” he said. “If we’re not taking care of Nicʔ, we’re not taking care of ourselves.”

Minerva Allen, an Assiniboine elder and language instructor at the college, made a similar point. “Water is not only life, it is holy,” she said. Traditional ceremonies, she recalled, included placing bundles of tobacco, meat, sweetgrass, sage, and food into the river to both feed and please the water. Camps were placed away from waterways to prevent pollution or damage to riparian environments.

• • •

These values persist, though the work of protection and conservation now requires new skills. To monitor waterways, the Nicʔ-Mní Center will rely on the expertise of Water Center co-directors Randall Werk, who teaches both environmental science and American Indian studies, and Dr. Liz McClain, who for more than two decades has taught a wide range of environmental science, life science and allied health courses at the college.

The center will also be supported by three STEM faculty: Dan Kinsey, life science instructor; Chelsea Morales, life science/allied health instructor; and Dr. Brian Grebliunas, environmental science instructor. Data collection and analysis will be supported by two lab technicians. Students will also participate in the center’s research.

Much of their work will focus on studying macroinvertebrates, which are small aquatic animals and insects—mayflies, stoneflies, and caddis flies, primarily— in their aquatic larval stages, explained KateLyn Goes Ahead Pretty, a current ANC student who researched the water quality of several reservation streams as part of her academic program. Presenting her findings at the Water Forum, she explained that the number and variety of macroinvertebrates provide clues to the health of waterways. “A higher count is a sign of good, clean water.” A lower count is evidence of a stressed environment.

Macroinvertebrates are collected in kick nets from both impacted streams and healthy “control” sites. Back at the college’s water lab, staff and students separate and identify the samples under microscopes. Her research indicates that some creeks are showing signs of regeneration. King Creek’s water is no longer red, for example, and insect life is returning. But all streams flowing out of the mine remain impacted and South Bighorn Creek, in particular, “has shown hardly any improvement over the years,” said Goes Ahead Pretty. Even under the best of circumstances, it will take many years to repair the damage done. The legacy of the mine’s contamination will be felt for generations.

Looking to the future, Aaniiih Nakoda College hopes that the Water Center will also become a clearinghouse for public education and policy—a place where credible research will be both generated and shared with tribal leaders and community members.

The need for public engagement is especially important as the tribe works to finalize a water rights settlement that must be approved by both the tribe and Congress. If passed, the settlement will enforce a previously negotiated “Water Compact” with the state of Montana and provide federal funding for development of water resources.

However, the settlement is a highly contentious issue within the reservation. While the Winters Doctrine established the tribes’ right to water, the amount of water it will receive from rivers, reservoirs, and even the reservation’s groundwater must be negotiated with the state. This means that the tribe must accurately predict future needs and also accept the state’s role in forming tribal water policy.

Tribal Chairman Andrew Werk Jr. supports the negotiated settlement, asserting that it represents the best possible agreement in a complex legal and political context. Other tribal members oppose the settlement, however, arguing, in part, that it weakens tribal sovereignty. Why, they ask, should the tribe negotiate for water that is theirs?

Both views were respectfully discussed at the Water Forum, supported by presentations from researchers and members of a consulting firm hired to study and negotiate a settlement on behalf of the tribe. Though no resolution was found that day, it helped build public awareness of the complex issues—political, cultural, and hydrologic—involved in any discussion of water. Chairman Werk, who said he was “frustrated by lack of engagement” over water issues within the tribe, hoped that it will help speed resolution of this long-standing debate.

• • •

Water represents many different things: For politicians it’s an economic resource, necessary for growth and development. For engineers, it’s a natural resource to be captured, stored, and moved. For many others, including Native peoples, water is also an environmental and spiritual resource: Essential for life, it is a symbol of life.

The role of the Nicʔ-Mní Center—rarely found in the factionalized world of water policy—is to consider the role of water in both human and ecological contexts. Research conducted by the center will offer reliable insight into the health of the reservation’s waterways. But its work is also guided by the tribes’ heritage, and reflects an awareness that the wants and needs of the current generation must be balanced with the needs of those to come.

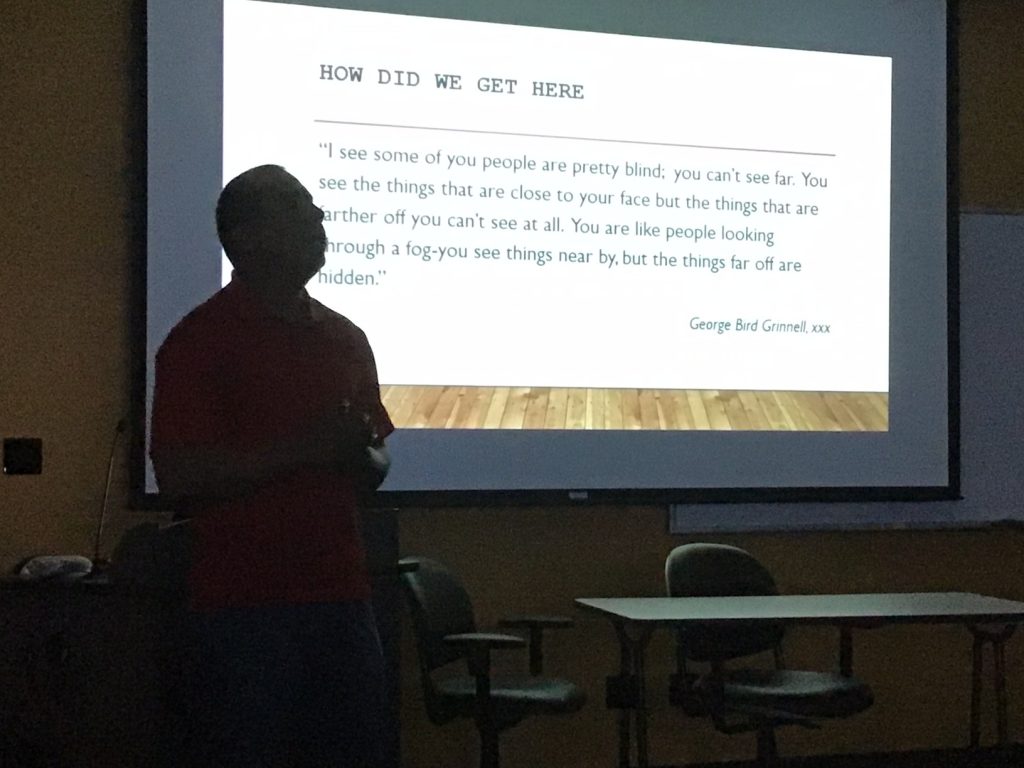

This role was not always understood or respected. More than a century ago, the naturalist George Bird Grinnell, negotiating on behalf of the federal government for the sale of gold-rich land, chided tribal members for what he said was their short-term thinking.

“I see that some of you are pretty blind, you can’t see far,” he said. “You see the things that are close to your face, but the things that are further off you can’t see at all. You are like people looking through a fog, you see things nearby, but the things far off are hidden.”

Selling the land would, he implied, help the tribe secure a more prosperous future. But it turns out that Grinnell—and the values he represented—was the most blind. Focusing on short term wealth over long term stewardship led, only a few generations later, to tainted water and a despoiled landscape that is costing millions of dollars to manage. It’s now up to the Fort Belknap tribe to make things right.

Paul Boyer is editor of Native Science Report.

Wonderful article Paul. Thank you for this most important story about Aaniiih Nakoda College and the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation.

I plan to use this great article with my Environmental Science class at Hays-Lodge Pole High School (5 miles from the mine) but I don’t see a date on it. When was it written?

Rod, The story was from the summer of 2019. Thanks for your interest and good work.

Never mind – I can see in the URL that the article is from September 2019.