As director of technology for the Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association, Matthew Rantanen has worked for twenty years to bridge the digital divide for Native communities nationwide.

By Katie Scarlett Brandt

Matthew Rantanen spent the summer before his senior year at Washington State University working to save up for a computer. A friend had convinced him that as graphic design students, they needed to learn computers or they wouldn’t land design jobs after graduation. It was 1991—when computers were relatively new, and the Internet was not yet an integral part of daily life.

Rantanen saved $3,500 that summer and bought a computer for the coming semester. Most of his class stuck with arranging text and images by hand. His foresight paid off. Out of a class of 26 graphic design students, Rantanen said, only he and the other two students who worked from their own computers went on to careers in graphic design.

However, it was his interest in technology, and prescient understanding of its potential, that ultimately shaped his career. For the past twenty years, Rantanen, who is of Cree, Norwegian, and Finnish descent, has served as director of technology for the Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association. He is also co-chair on the Technology Task force for the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), a former member of the FCC’s Native Nations Broadband Task Force, and was formerly board chair of Native Public Media.

In these and other positions, Rantanen works to bring the internet to tribes across the U.S. and helps guide tribal governments as they develop plans for digital access. Internet2, a non-profit consortium founded in 1996 by higher education institutions, awarded Rantanen the 2020 Rose-Werle Award for “extraordinary individual contributions that have made demonstrable impacts on the formal and informal education community by extending advanced networking, content, and services to community anchors nationwide.”

The award announcement hailed Rantanen’s recent work to connect fourteen Native American tribes in Southern California to the research and education network, CENIC through the international peering fabric, Pacific Wave. “This new connection enables their tribal libraries, scientific research facilities, and cultural preservation institutions to collaborate with partners across the state, the nation, and the world,” the award announcement stated.

Rantanen, who said he prefers to focus on the work, not the awards, calls himself, “a big-picture person. I can bring people together from all walks of life, all levels of understanding, and get their heads around the future of technology in their space. I make connections between industry, community, policy and funding, advocacy. I have enough information to be dangerous in all areas.”

That broad view fuels Rantanen’s drive to educate tribes and policymakers, to help both sides understand the process and value behind connecting everyone to the internet.

“Everyone deserves the same opportunities. Just because you live in town you get broadband, and people in rural areas don’t. Screw that,” Rantanen said.

For government policymakers, “There’s a trust responsibility of the federal government to deliver services,” Rantanen said, including internet access as a crucial utility. “Yet, only 70 percent of households on reservations can call 911. Cell phone coverage is poor as well.” Even in San Diego County, where Rantanen lives, “people go home and turn on generators to run power to their house because the power company hasn’t supplied to them.”

For tribes, the future of technology and internet access take many forms — from managing their own communications and opening up to other businesses, to tribal infrastructure and information security. It also connects individual tribal members to the global economy and opportunities.

“Tribes are always about self-determination and self-governance. Having a plan is ownership of that digital sovereignty,” Rantanen said. He envisions connectivity plans that give tribes a chance to control their online presence and create an internal communication platform, enabling cultural efforts such as language preservation.

For craft-driven communities, such as the Navajo, internet access connects members to a world of potential customers. Drive through Navajo Nation, and you can’t miss the roadside stalls that dot the highways. “That’s their market space, their storefront window. But (due to Covid-19) that hasn’t been their market space for the last solid year,” Rantanen said. “There’s a really good chance that they are destitute right now. You have to have that ability to be out there so people can understand your product, your opportunity.”

“Everyone deserves the same opportunities,” Rantanen said. “Just because you live in town you get broadband, and people in rural areas don’t. Screw that.”

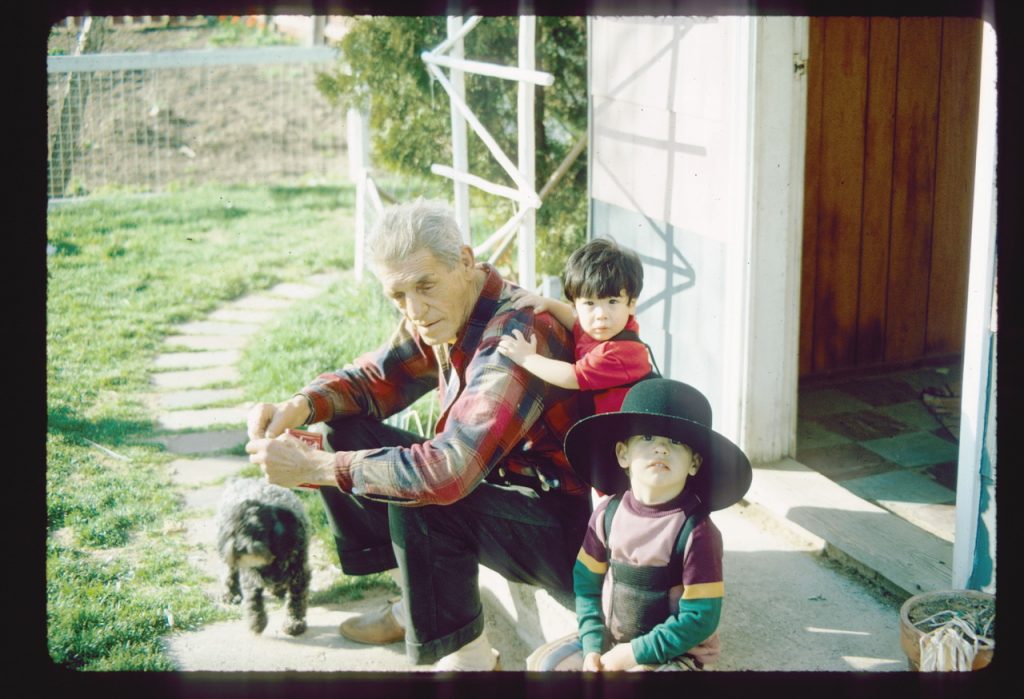

Rantanen himself grew up during a time when few people had internet access. He was born in 1969, during the Vietnam War, shortly after his dad had enlisted in the air force as a veterinarian.

“I was born in Washington D.C., at Walter Reed Army Medical, where the presidents go,” Rantanen said. Shortly thereafter, his family returned to Washington State, and his dad left for Vietnam. Both sides of Rantanen’s extended family had lived in Washington and Idaho for over a century, the Cree side of his dad’s family having traveled south from Alberta.

While his father was overseas, Rantanen’s mother taught high school math. After the war, the family moved to Germany for three years, returning stateside to San Antonio, Texas, where Rantanen enrolled in first grade. The next year, they were back in Pullman, Washington. Rantanen’s father taught radiology at the veterinary school for six years.

In eighth grade, Rantanen got to school at 6 a.m. so he could learn to weld. He built a mini motorcycle from scratch — an experience that taught him valuable lessons early on. “I never shy away from much. It’s just a process to get through,” he said.

The family next moved east to Kentucky, where Rantanen’s father started a practice performing ultrasound scans on racehorses. Meanwhile, Rantanen’s mother had switched from mathematics to interior design, and began using her second degree in landscape architecture.

“I always had these great examples in front of me,” Rantanen said of his parents. “And all of this moving around made me a little bit of who I am today. I never had any fear of talking to adults. I met my dad’s colleagues before I met any kids. It prepped me for just being able to stand up in front of 1,000 people on a stage and talk to anybody. It doesn’t matter your work status or your social status.”

And Rantanen has done a lot of public speaking — in and out of the White House, on international stages, and with tribal leaders.

After high school, Rantanen returned to Washington for college at Washington State University. He partied through his freshman year. He was in the perfect place, at the perfect time for the birth of the grunge music movement. He remembers going to intimate Soundgarden and Alice in Chains shows for $3 donations to Amnesty International. Then, Rantanen happened upon a Native American literature class, full of “sad and oppressive but also amazing stories that helped me re-anchor myself in college, in the scholastic part,” he said.

Over the next three years, Rantanen dove into the fine arts, with a focus on graphic design. He minored in printmaking, photography, and sculpture, which changed the way he thought about two-dimensional design. “Sculpture made my 2D design different because I was thinking in 3D a lot, and applying that 3D to the 2D made my work look different,” Rantanen said.

That ability to think differently and see beyond current realities continues to serve Rantanen well. After college, he moved to San Diego and started working as a designer at Blue Mountain Greeting Cards, a small start-up company at the time. As happens with start-ups, Rantanen took on many roles, including setting up new offices and server networks as the company expanded. He moved to his own office in San Francisco, hiring developers to work under him.

When the dotcom bubble burst in 2001, Rantanen was laid off. But he wasn’t out of work for long. A former Blue Mountain colleague called him, saying a contact, the Southern California Tribal Chairmen’s Association, needed help connecting tribes in southern California to the internet. Rantanen headed back down to San Diego for an interview.

They ended up hiring Rantanen on the spot to teach tribes how to build and use community web portals. One of his first projects involved building a network with a portion of a $5 million Hewlett Packard grant, being mentored by the High Performance Research and Education Network, a National Science Foundation-funded initiative out of the UC-San Diego.

The network built out technology to track earthquakes and report them to the university. Rantanen’s project used that guidance and the Hewlett Packard grant money to connect tribes, providing internet connectivity to tribal operations and schools for email. As he worked, Rantanen saw an entire ecosystem unfold before him, and he helped tribal leaders understand that the network funding they had could only go so far.

“I started to realize we didn’t have access to certain funding. I started getting into spheres of policy and government, met with senators, talked with the FCC,” Rantanen said. He created a brochure called “And Tribal Communities,” which he handed out to the people he met with, explaining the challenges and highlighting the value of connecting tribes to broadband.

The main challenge, even two decades later, is that when the U.S. began laying broadband fiber across the country, the telecom companies with which they contracted for installation largely skipped rural America. They bypassed small towns and reservations, trying to build faster by skipping complex areas with various owners and land designations.

As a result, the biggest internet access challenge that tribes face today, Rantanen said, “is the missing 8,000 middle miles” of internet connectivity in the U.S. This leaves tribes behind, literally in another century.

Rantanen isn’t going to let tribes be forgotten. Just like the days he spent at Blue Mountain during its start-up phase, he said, “I get energized by that start-up atmosphere of a community that wants to champion change.”

And he has a list of changes he’d like to see happen, starting with better financial traction. The second CARES Act allocated $1 billion for tribal broadband, “but it’s a $7 billion project.” Instead, Rantanen advocates for a standard, dedicated amount of money to address all tribal needs, not just broadband.

Federal and local governments also need to meaningfully engage tribes. With telecommunications specifically, California has taken the positive step of asking for tribal sign off and engagement saying the tribe supports an outside company’s efforts before the state matches any funding.

“The second CARES Act allocated $1 billion for tribal broadband, “but it’s a $7 billion project,” Rantanen said.

Rantanen argues there also needs to be an Office of Native Affairs at the federal level. The FCC has such an office, but Rantanen calls it a placeholder in its current form with no real tribal influence, “just lifer FCC staff not really dedicated to the tribal perspective.”

Other departments need tribal engagement too, he said. “It’s government-to-government engagement, that responsibility they have in that trust relationship.”

The government also needs to cut down on the time it takes to process permits. “If America wants a densified fiber grid to support all its people, it has to smooth out those processes that make it take a year to get a permit,” Rantanen said. “It takes a week to do the permit, but there’s so much bureaucratic red tape that makes it take a year.”

He has hope with Deb Haaland as Secretary of the Interior because “she’s a champion of broadband, and the Interior Department is responsible for permitting a lot of broadband builds, fiber in the ground.”

Rantanen would also like to see the government release more spectrum—the airwaves that enable internet connectivity. And he wants tribes to have the first chance to claim ownership of those airwaves over their lands, as happened previously with FM radio, and most recently, with 2.5 GHz spectrum for broadband.

Perhaps most importantly, Rantanen envisions more connectivity of people and projects, across disciplines. “We’re stuck in all these silos that have been imposed on us by the federal government. Those silos have to be broken down.” As one example, he said, “People have to be able to use federal funding for housing and broadband at the same time to get the results. We should be able to build a HUD (Housing and Urban Development) home with a smart design. It’s so easy to do up front, and cost is minimal on the front end.”

Covid-19 has proven just how important that connectivity is — from internet connectivity to the face-to-face connectivity that so many tribes rely on to get business done. “The human interaction has really changed,” Rantanen said of the past year.

In his own interactions, he thinks back to his father and what he learned from tagging along with him as a child to horse barns in Kentucky. “He was gracious and interactive with everybody there, from people mucking stalls to groomers. And these would be barns that are nicer than any house I’ve ever lived. He took the time to talk to everybody. That really informed who I am in this space,” Rantanen said.

Rantanen hopes those connections and the work that results from them will speak for itself after he’s gone. “I think people will be excited about what happened,” he said.

Katie Scarlett Brandt is a freelance writer based in Chicago. She is a regular contributor to Native Science Report.

Published April 6, 2021. Updated April 7, 2021

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications of new posts by email