Many tribal colleges prepare students for nursing and allied health professions. In the wake of Covid-19, it’s clear that they should do even more.

By Shazia Tabassum Hakim

According to the U.S. Department of Education, there are currently 32 fully accredited tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) in the United States, with one formal candidate for accreditation. Three are in Associate Status. According to the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, these TCUs offer 358 total programs, including 181 associate degree programs, 40 bachelor’s degree programs, and 5 master’s degree programs, as well as apprenticeships, diplomas, and certificates. Despite this diversity, however, all TCUs are communally lacking allied healthcare and medicine-related programs. Overall, only 17 TCUs offer programs related to allied healthcare or other professions of medical importance. These programs include 23 associate, 27 certificate, 1 diploma, and 1 bachelor’s level program. The Cherokee nation’s college of medicine in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, is a new addition to the list.

Closer examination reveals that, out of 23 associate programs offered at TCUs, 11 are in nursing or pre-nursing, and 6 are in allied health science. Dental health therapy, medical laboratory technician, and medical administrative assistant have one program each. Out of 27 certificate programs offered at TCUs, 7 are in medical office assistant, 3 in medical coding and billing, 8 in nursing assistant, 2 in allied health, 2 in emergency medical services or paramedics, 1 in optical lab technology, 1 in phlebotomy, 1 in medical assistant, 1 in dental assisting, and 1 in alcohol and drug abuse. Additionally, a bachelor’s in nursing program is offered by Salish Kootenai College, and a diploma in practical nursing is offered by Fond du lac Tribal and Community College. Approximately 80% of TCUs offering these medically important programs are located in North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Michigan and Wisconsin.

According to the 2010 Decennial Census, 0.9% of the U.S. population, or 2.9 million people, identified as American Indian or Alaska Native alone, while 1.7% of the U.S. population, or 5.2 million people, identified as American Indian or Alaska Native alone or in combination with another race. This is an increase since 2000 of over 39%, while the latest numbers from 2020 indicate a total population of 6.79 million Native Americans. If we compare these numbers with the accessibility of medically important or allied healthcare programs to our tribal youth and communities we can clearly understand the huge gap and lack of Native Americans and Alaska Natives in these fields.

The SARS-CoV-II (Covid-19) pandemic has only highlighted longstanding health care disparities within Native communities. For example, when compared to all other U.S. ethnic and racial groups, American Indians and Alaska Natives have a lower life expectancy by 5.5 years. This includes higher rates of death from chronic illness, including diabetes, chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, mellitus, and suicide. Additionally, American Indians and Alaska Natives die of heart disease at a rate 1.3 times higher than all other races; diabetes at a rate of 3.2 times higher; chronic liver disease and cirrhosis at a rate of 4.6 times higher; and, intentional self-harm and suicide at a rate of 1.7 times higher.

A major cause of these healthcare related problems is unavailability of a locally trained workforce that could be more aware of local culture, traditions, language and environment—people who are more mindful of the problems associated with living conditions within these remote and rural communities. We are lacking personnel who have a passion to serve their own communities, families, and friends close to their homes.

Since March 17, 2020 when the first officially confirmed Covid-19 case was reported on the Navajo Nation, the Nation has faced persistent barriers in its response. There are shortages of health care providers, a limited healthcare infrastructure, and a scarcity of advanced clinical diagnostic facilities, all of which limit access to care. In addition, the Nation faces higher rates of underlying disorders, a lack of clean water, and a shortage of healthy food, especially fresh fruits and vegetables. The elderly who live on the Navajo Nation are the most affected group; the hardships they are facing are exacerbated by language barriers.

Overall, as of April 14, 2021, there were 30,269 confirmed positive cases and 1,262 deaths due to Covid-19 on the Navajo reservation, with the majority between 60-80 years. If we look at available demographics, out of the estimated 5.2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) in the U.S., about 3,400 are physicians, which is just 0.4% of the physician workforce, according to a 2018 AMA Council on Medical Education report, “Study of Declining Native American Medical Student Enrollment.” According to the “Minority Nurses” survey, there are 2,824,641 Registered Nurses (RNs) and 690,038 Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) in the US. Of these, only 11,300 (0.4%) are American Indian/Alaskan Native RNs and 4,100 (0.6%) LPNs. Another survey report from zippia.com indicates that the most common ethnicity among medical laboratory scientists is White, comprising 58.8% of all medical laboratory scientists. Comparatively, 14.9% are Hispanic or Latino, 11.6% are Black or African American, 11.5% are Asian, and 0.7% NA/AI. Similarly, 63.4% of all quality control technicians are White. Comparatively, 16.0% are Hispanic or Latino, 8.9% are Black or African American, 8.7% are Asian, and only 0.5% are NA/AI.

For those of us working with tribal colleges, it is our responsibility to look into the needs of our communities. We have to introduce a greater variety of allied healthcare and medically important programs in our institutions.

So, the question that comes to our mind is, Are Native/Indigenous communities incompatible with healthcare fields? Definitely, the answer is “no.” The “Medicine Wheel,” or “Sacred Hoop,” has been used by generations of various indigenous tribes for health and healing. It symbolizes the Four Directions, as well as Father Sky, Mother Earth, and Spirit Tree—all of which represent dimensions of health and the cycles of life. Medicine men or women have always been a very important part of Native American tribes. Traditional wisdom and knowledge passed from generation to generation by the medicine men or women has tremendous value within tribal communities and culture because people find security and mental peace leading to maintenance of good mental health and a sense of harmony. These traditional medicine men or women are unique, unparalleled, and essential; they are some of the most competent individuals with a tribe.

This helps us to ask what we are missing. What do we need to improve? For those of us working with tribal colleges, it is our responsibility to look into the needs of our communities. We have to introduce a greater variety of allied healthcare and medically important programs in our institutions. We need to increase the number of NA/AI healthcare professionals in almost every field of medicine and allied healthcare to meet local needs and to fill the gap. Data discussed earlier clearly emphasize that everywhere current statistics range between 0.4 – 0.7 %. We have to bring it up, by at least 1% in next 10 years, if we really are serious about healthcare for our AN/AI communities and our elders. So again, question comes that how?

Diné College has played the role as pioneer before when in 1968 Diné, Inc., an organization established by Native American political and education leaders, founded Navajo Community College (later renamed Diné College). This was the first tribal college to be created on an American Indian reservation. Since then the number of tribal colleges has increased steadily in the United States. The Navajo Community College Act of 1971, which provided federal funding for nation’s only indigenous post-secondary educations at that time, was developed after establishment of Navajo community College. That led further many other federal policies and procedures for Native controlled institutions. As of 2001, 32 tribal colleges have emerged, created by American Indian tribes for American Indians. These colleges are located in areas with large concentrations of Native Americans, principally in the upper Midwest, the Pacific Northwest, and the Southwest.

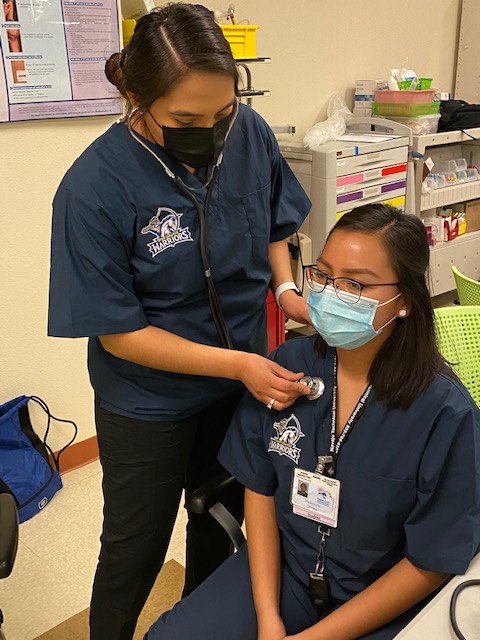

At present, Diné College has six campuses and centers across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah that are offering over 20 degree programs and more than 385 courses, mainly to the Navajo youth (99%). Our Public Health program, led by Dr. Mark Bauer, is already a symbol of success among Navajo communities and youth, but we still need to do more. The Board of Regents and Executive Committee of Diné College under the leadership of Board Director Mr. Greg Bigman, college President Dr. Charles Monty Roessel, Provost Dr. Geraldine Garrity and Dean of STEM Mr. James Tutt, along with the Biomedical Sciences faculty from the School of STEM, are looking at this whole situation critically and considering the importance of healthcare related programs and training of local healthcare workforce. With this background, Diné College started its first yearlong Certificate in Medical Assistant program in fall 2020 in collaboration with the Tuba City Regional Health Care Corporation, which was a timely decision in light of the Covid-19 pandemic. The first cohort of CMA program will be graduating in fall 2021.

We did not stop there. On February 19, 2021 Diné College, School of STEM hosted a one day virtual conference on “Emerging infections & Tribal Communities: What we learned from COVID-19 Pandemic?” The conference was sponsored by American Society for Microbiology under the ASM conference grant award received by Dr. Shazia Hakim, Professor Dr. deSoto, and Ms. Barbara Klein. Choosing Diné College as the venue for that conference provided an exceptional opportunity to underscore the work which has happened, is ongoing, and is planned to occur, and to raise the visibility of both Navajo Nation and Diné College as leaders in understanding and responding to the situations like this pandemic with brave hearts, learned faculty and staff, enthusiastic students and warrior approach not only in Navajo Nation or tribal communities but throughout North America.

Overall, two sessions covered fourteen presentations given by Navajo Nation President Mr. Jonathan Nez, CDC’s Dr. Leandris Liburd, scientists and tribal leaders from the US and Canada, who have brilliant scientific backgrounds and are currently working on the front lines of the Covid-19 crises. The conference, which was also streamed live on Facebook, drew a large audience despite of time zone differences. Viewers represented the Navajo Nation and other tribal communities of North America, including Apache, Pueblo, Cherokee, Hopi, Cree, Metis, and Nipissing, It also attracted many non-tribal viewers from the US, Canada, Australia, Egypt, New Zealand, Kenya, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, India, Srilanka, UAE, Bangladesh, and China. Diné College students were also well represented. Most of the responses we received from our attendees were very appreciative and encouraging and also signifying the importance of similar activities within tribal communities and the necessity of awareness and availability of latest healthcare facilities within tribal communities.

In addition, Diné College’s school of STEM is ready to launch its first ever BS in Biomedical Science program in fall 2021. The program emphasizes biomedical health promotion for American Natives and Alaskan Indians especially Navajo youth. Our graduates will have opportunities to work at agencies and organizations within the reservation, including the IHS and tribally contracted healthcare facilities, as well as the Navajo Utility Authority, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Health, and Epidemiology Center. They will also will be able to join many other scientific industries and higher education institutions and research facilities outside the reservation, or anywhere else within the country or the world. The program will help our tribal youth to develop extraordinary professional growth and technical skills at their own local campuses and centers close to their home. We are hoping that our graduates will pave their way to medicine, nursing, pharmacy, clinical laboratories, healthcare quality control, healthcare statistics and many other allied healthcare professions. They will fill the gap we have between our community members and healthcare providers. They will be a ray of hope for both our current and coming generations of warriors. We at Diné College, school of STEM, inviting our Native American and Indigenous youth to join us to move forward with the warrior sprit. Further details on the program are available at Diné College website.

Dr. Shazia Tabassum Hakim, PhD., is a Biomedical Sciences (Microbiology) professor at the School of STEM, Diné College, Tuba City campus, Arizona.

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications of new posts by email

I am so proud of Dr. Hakim and her achievements and contributions. Especially her work at places where it is desperately needed.