To attract and support Native students in science, STEM faculty can—and should—more fully integrate western and Native worldviews, according educator and author Dr. Gregory Cajete.

By Melanie Lenart

For almost four decades, Dr. Gregory Cajete has been involved in efforts to attract Native students to STEM. During a virtual talk in mid-April hosted by Leech Lake Tribal College, the longtime educator and researcher praised the work of tribal colleges, while arguing that they can do even more to support Native students by including indigenous cultural references and values in the science curriculum.

“One of the places where that kind of education can be done and done well, I think, is tribal colleges,” Cajete told the educators and others during his keynote talk, Creating Culturally Responsive Indigenous Science Education Curriculum. “I know that this is going on in many of the tribal colleges already, and has been going on for a long time. But there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done.”

Cajete is a professor emeritus with the University of New Mexico, where he taught in the College of Education and served as director of Native American Studies. His Ph.D. from International College in Los Angeles involved social science education with an emphasis in Native American Studies. His five books include Igniting the Sparkle: An Indigenous Science Education Curriculum Model.

Cajete first experienced the challenge of teaching science to Native students in 1974 when he was recruited to teach biology at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the homeland of his own Tewa-speaking Pueblo tribe. He said the science courses required for every undergraduate student were posing barriers to graduation for many of the IAIA students

“They were intuitive enough to realize that science as it was being taught in the traditional western science way was just not what they wanted or what they could understand,” he said. An artist himself—he continues to work with ceramics and metal—Cajete started designing culturally responsive curricula based on indigenous perspectives of the natural world.

IAIA students weren’t the only ones shying away from science. Even today, the proportion of Native American and Alaska Natives pursuing science degrees tends to fall well below the 1.2% of the population that they represent. The proportion of Native American faculty members in STEM—Science, Technology, Engineering and Math—falls even lower, leaving the students who do pursue such degrees with few relatable mentors. “The way we have taught science, the way we continue to teach science in some cases, actually lends itself to the distortion of many of our students’ view of science and also impacts their participation in science-related fields,” he said.

Despite claims of objectivity, western science inherently reflects western culture. It focuses on classification and on studying the parts, and favors learners who are analytical and verbal.

Cajete has been on a quest to change this equation since he started tackling the problem, teaching revamped biology courses while simultaneously pursuing his doctoral degree in education with the encouragement and support of IAIA administrators. His dissertation research became his book Native Science: Natural laws of Interdependence, which provides detailed background on the concepts and guides educators on the process of revising curriculum for college science courses.

Despite claims of objectivity, western science inherently reflects western culture, he noted. It focuses on classification and on studying the parts, and favors learners who are analytical and verbal. Meanwhile, indigenous cultures tend to emphasize visual over verbal paths to knowledge, lean toward synthesizing rather than analyzing, and take a more holistic view rather than focusing on the parts.

The end result is a clash in worldviews that creates a barrier for indigenous students pursing science, Cajete said. He illustrated this confrontation by making his hands into fists—one for the western materialistic view of science and another for the indigenous approach—and pressing them against each other.

“In conflict, you have this dynamic tension. Usually it’s a give and take, give and take,” he said, moving his fists back and forth. “But what we are actually really after is this—integration.” With that, he entwined his fingers together, suggesting a meshing of the two worldviews. “In my view, the use of indigenous content will facilitate these goals.”

In the talk and in his 2020 Tribal College Journal article, Cajete describes how he adapted a curriculum model developed by Robert Zais in 1976 to facilitate integration of these worldviews. Instead of starting with the instructor’s aims and goals for a class, Cajete’s adaptation turns the teaching of science “on its head” by considering the learners and their culture first when approaching curriculum development.

For instance, many indigenous thinkers embrace subjectivity, finding it easier to learn something when there’s a reason and context for it—such as learning a particular skill to accomplish something that will help their tribe. Putting learning into this context can make it more relevant to students, as can grounding the material in a cultural foundation.

At IAIA, he started including cultural references and encouraging the students to approach their learning about animals by making artwork about them, for example. Building on cultural foundations, he would move into covering the material required for western science as well.

An integrated STEM curriculum can honor both western and indigenous worldviews, Cajete said. “While indigenous students are learning western science, they’re also building on their own ancestral systems of knowledge.”

“You still incorporate the teaching of principles and forms and classification structures, but you do it in some creative and holistically focused ways,” he explained. “And you use a lot of Native traditions, exemplifications, histories, Native art, and examples of how Native people related to the land and to the environment and to the cosmos.”

Cajete said he also adapted consideration of the “scientific method” to the “creative process method,” which he broke down into the following categories:

- Insight

- Preparation/immersion

- Experimentation

- Presentation

With measures like this, he found students were able to think holistically and creatively about science, in a way that transferred into other areas of study as well.

“While indigenous students are learning western science, they’re also building on their own ancestral systems of knowledge,” he said. “And non-indigenous students taking this kind of science course are considering other cultural ways of knowing nature that enhances their knowledge gained from western science. So there’s a two-way street, a two-way process going.”

The cultural context provided by tribal colleges and universities can help students over the long term in their academic pursuits and careers, as does the availability of relatable mentors. With about 45 percent of TCU faculty identifying as Native American or Alaskan Native, compared to less than 1 percent at mainstream institutions, students can find many relevant mentors as well as a relevant cultural context. This foundation helps: Almost four times as many Native students (38 percent) who pursued their bachelor’s degree after attending a TCU succeeded in obtained their bachelor’s degrees, compared to 10 percent in general for those who go straight to a four-year non-tribal institution, according to one 2019 research review.

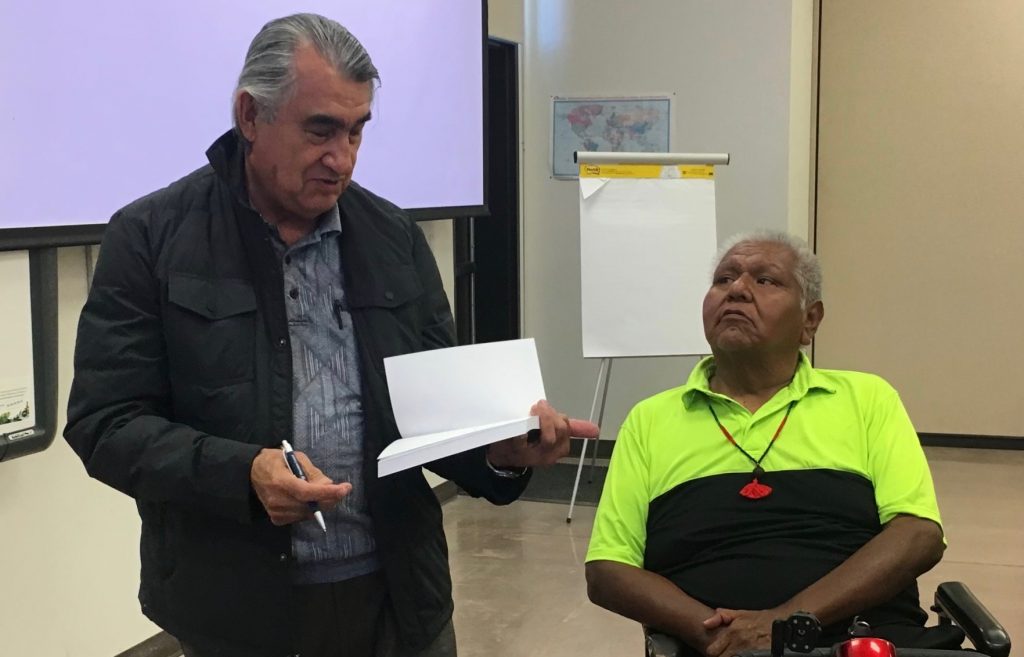

Now a professor emeritus from the University of New Mexico, Cajete continues to guide curriculum development through webinars and workshops. He has been leading grant-supported annual curriculum development workshops at Tohono O’odham Community College since 2019 at the invitation of Science and Health Chair and Science Instructor Teresa Newberry, who spoke of one aspect of the program at the mid-April conference.

Dr. Newberry presented on TOCC efforts to integrate cultural values into science curriculum, including in online courses. The five-year National Science Foundation grant that she secured to support the workshop with Cajete also supports a variety of related efforts, including lectures and faculty and student support by Tohono O’odham cultural expert Camillus Lopez.

Lopez teaches the O’odham perspective of the science under discussion, including 15-minute or so videos for the online iteration of a keystone course, Environmental Biology. For example, Newberry explained, during the section on biogeochemical cycles, Lopez shares the O’odham views of the four elements: earth, air, fire and water.

The brief videos inspire discussion among the now-international students, Newberry said, adding, “The students become teachers to each other and it creates a sense of community.”

Cajete acknowledged that shifting from face-to-face interactions to distance learning poses its own challenges, but suggested that making relevant cultural connections remains essential for online science courses to help integrate western and indigenous science.

“We know that significant learning tends to be directly related to the extent of personal degree of relevance a student perceives in the educational material presented,” he said. “This has implications also for online learning because if the examples or the kinds of assignments or readings that you’re giving students in online learning situations is not relevant to them, it’s not going to stick with them.”

On a positive note, the material generated for the online courses—so essential during the pandemic—may continue to be useful well beyond recovery for future classes at tribal colleges and universities. For instance, the presentations from the Leech Lake Tribal College conference, which had originally been conceived as an in-person exchange, remain available as an online resource for registrants of Waasamoogikinwaa’amaading: A Virtual Conference on Post-Pandemic Online and Distance Learning at Tribal Colleges.

Many instructors had to shift to online teaching during the pandemic, essentially reinventing their teaching styles. Cajete congratulated educators for their successes and expressed appreciation for those making the extra effort to integrate western science with Native science.

“In some ways, Native science is also being reinvented as we integrate some of our thoughts and perspectives with western science and begin to move forward in that way as well,” he said. “I’m hoping that a lot of young, Native people who are being now trained in tribal colleges are going to take on the challenge of really beginning to bring Native science into its own in the next generation.”

Melanie Lenart has been a regular contributor to Native Science Report since 2020. From 2015 through the spring of 2020, she worked as a science faculty member at Tohono O’odham Community College. There she participated in a 2019 workshop led by Gregory Cajete that helped inspire some of the efforts by TOCC.

Published May 5, 2021

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications of new posts by email

Interesting approach to learning STEM. As a Native American of Navajo/Meskwaki ancestry, I was born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona. I developed an appreciation for STEM through Art, making it STEAM. It was the simple drawing of a ladder done by my mother that got me interested. I learned mechanical aptitude from my father. Also, through observation of my surroundings, I developed interests in meteorology and geology. Through TV and movies, I developed a lifetime interest in aircraft, aircraft systems, weaponry and aerospace. The movies and programs that influenced me were Hindenburg, The Spirit of St. Louis, Midway and Baa Baa Black Sheep. When boys my age were drawing normal things that boys draw, I was drawing the electrical distribution infrastructure I saw, mechanisms and WWII aircraft. That led to model building, where I learned of aircraft systems and weaponry.

Although I never had time to earn a degree, I worked for employers like Honeywell, Boeing and Intel by adapting what I learned and continuing to learn.

One of the reasons I brought up art, was noting some of the drawings displayed at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center. One time, while at a bar in Phoenix, another Native man came up to me and did a pencil drawing for me. What bothered me was what if he had different educational opportunities and encouragement. Who knows how things could of turned out for him.