Tribal researchers are studying the impact of mining and oil drilling on reservation lands—and working to repair the damage done

By Katie Scarlett Brandt

This is part two of a three-part series on how tribes are managing their vast energy resources. Part I examined competing arguments for and against mining and drilling. Part III will examine how tribes and their colleges are leading the way to a green energy future.

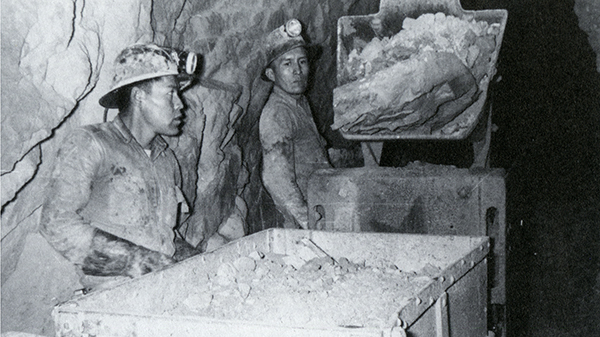

Perry Charley’s research stemmed from tragedy. As a boy growing up on the Navajo Reservation in the 1950s, he remembers seeing a green van and his father—a uranium miner who worked underground—waiting in line beside it to be examined. Charley didn’t know it at the time, but his father and the other miners were part of a study.

Aware that exposure to radioactive ore correlated with increased rates of lung cancer, the federal government sent scientists to the Navajo Reservation to measure radiation exposure among Navajo miners and monitor their health.

The scientists didn’t tell the miners why they were being examined, nor did they widely share their findings. In 1959, nine years after the study began, the Public Health Service distributed pamphlets to miners mentioning a risk of cancer but downplaying any concerns. It remains unclear how many pamphlets they gave out and whether the miners understood the document, which was written in English, a language many tribal members did not speak or read.

For Charley’s father, it was too little and came too late. He died in 1986 from lung cancer and associated lung diseases: silicosis, pulmonary fibrosis, radiation fibrosis. As his lungs failed, he fell into a six-year coma. He had worked as a miner for 27 years.

• • •

Charley’s childhood memory illustrates the promise and pitfalls of tribal energy development. Reservation lands sit on an estimated one-third of the United States’ oil, coal, natural gas, and uranium. These resources can provide needed jobs and revenue. But mining and drilling also pose potentially serious risks to both individuals and the environment.

These trade-offs are real, but not always understood when contracts were signed. Relying on promises from industries that profit from leases, or federal agencies that bury inconvenient research findings, tribes and individual tribal members did not always have information needed to make informed decisions.

For Charley, that hard truth came many years after he saw his father standing beside the green van. Searching for information about the now infamous study, he and a colleague happened across a list of 197 research participants. There, Charley spotted his father: his name, his date of birth–and his exposure levels.

“The government knew for certain these miners would die,” he said. “They were basically on a death watch.”

In this new era of tribal empowerment, however, Native communities are taking a more active role in monitoring and managing their natural resources. Increasingly, this work is led by researchers, faculty, and students at tribally controlled colleges. On the Navajo Nation, for example, Charley now serves as director and senior scientist at Diné College’s Environmental Outreach and Research Institute, where he has focused for the past 30 years on the lasting impact of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation’s water, plants, animals, and people.

Part of the work involves locating old mine sites and documenting the damage done.Between 1944 and 1986 alone, land leases on the Navajo Nation enabled uranium mining corporations to extract 30 million tons of uranium ore. When the Cold War ended, companies abandoned 523 mines, without adequately covering them or disposing of the waste.

Much of that mining was done on behalf of the U.S. for weapons development, and in 2019, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced plans to spend $220 million over the next five years on cleaning up legacy uranium within the Navajo Nation. The agency is also involved in more than $1.7 billion in settlements to remediate areas with the highest risks of radiation exposure.

Today, the federal government is viewed as a research partner—but Navajo researchers are in charge. In September 2018, the agency awarded Diné College a $429,467 grant to study how abandoned uranium mines affect the Navajo’s cattle, sheep, and goats—their domestic meat sources. The EPA has awarded Diné College $809,481 for radiological risk research since 2016.

Charley is leading the study, and working with Diné College students as well as students and researchers at the University of New Mexico and Northern Arizona University. They will sample soil, water, and air, looking for numbers that can tell the story of how much impact the earth has sustained from uranium mining—and how much of the toxins left behind are moving up into the vegetation.

The group plans to collar animals to map their roaming range and track where they go for water and food. During the Navajo’s annual fall livestock butchering, Charley said people will donate their animals’ organs and tissues so his team can test them for heavy metal and radionuclide uptake. He will share the team’s findings with the EPA as well as Navajo agencies.

“Depending on what we find, it will dictate the design criteria for addressing mine waste and waste disposal strategies. That’s going to be critical,” Charley said. “A lot of our findings prompt the Navajo Nation to revise existing legislation. Methodologies are improved. Land use and other types of community development strategies are scrutinized much more closely, especially in mine areas.”

The livestock study will identify vegetation that can be planted where animals graze. Varieties and placement will depend on rooting depths and uranium presence. The main goal: to prevent livestock from eating toxic plants, which could then transfer to people as they consume the animals.

Charley has other goals for the study, too. Not only do animals eat vegetation, but traditional Navajo ceremonies also utilize plants, which means people could be directly exposed to uranium progeny during their spiritual practices. Because of those practices, the Navajo people have a general knowledge of the area’s foliage, and Charley has always encouraged non-Native risk assessors on the reservation to incorporate traditional Native American environmental knowledge into their assessments.

“They’ve resisted that, avoided it, ignored it,” Charley said. “Our work is very important at Diné College because it [could] revise our tribal laws. So our partners, when they come on to the Navajo Reservation, have no choice but to incorporate this into their risk assessment strategies.”

• • •

Charley has nurtured his relationship with federal agencies throughout the course of his career, but on Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota, Kerry Hartman is frustrated with his own experience with the EPA.

“I got caught in a case of classic bureaucratic backtracking and cover-up,” said Hartman, academic dean and environmental sciences professor at Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College on Fort Berthold Reservation.

In 2011, with support from the EPA, Hartman planned to analyze groundwater on the reservation for evidence of fracking fluids in the wake of Fort Berthold’s extensive oil development. The reservation is currently home to 1,861 active wells, which generate 22 percent of the state’s oil output. The EPA granted Hartman permission to duplicate a water study the agency had conducted about 90 miles away and gave him access to their labs. Hartman set about collecting 75 samples from groundwater wells on the reservation.

However, Hartman said the EPA terminated their agreement a year and a half later, in the middle of his study. He had recently delivered a second set of water samples to the agency’s lab in Golden, Colorado.

“I know it’s because we found something,” Hartman said. “I talked to a lab worker in Golden before he knew he wasn’t supposed to talk to me. They’d been ordered by Washington, D.C. based on the findings.”

The lab never supplied Hartman his results. But two years later, one of Hartman’s students resurrected the study. He used the same protocol followed by Hartman and the EPA, and worked with labs at Sitting Bull College and the University of North Dakota.

Results showed diesel and other fracking chemicals in “four or six of 30 or 40 wells,” Harman said, speaking from memory. “We wanted to do a re-test, a confirmation, but we were suddenly not granted access to those wells anymore.”

Hartman knows that his work has the power to change things. His water research stretches back to the 1980s, when he conducted an extensive research project with the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara (MHA) tribe. Most of Fort Berthold’s residents drank well water at the time, and complained of brown and black water or said that it left a coating on their coffee pots. The water had an odor, too.

“It wasn’t toxic,” Hartman said, “but the vast majority of rural water on the reservation is now piped thanks to that study. Very few people drink rural well water anymore.” Instead, a $14 million water system runs surface water through state-of-the-art treatment plants.

Currently, one of Hartman’s undergraduate students is researching flaring practices–the burning off of compounds during the refinery process—on the reservation. Without access to the flare pads, the student gathered snow from around the flares and sent it to the University of North Dakota for analysis.

“The flaring is very alarming and disgusting. We found a veritable cocktail of toxic compounds coming out of the flares, not to mention CO2 and other greenhouse gases, and C8, C10, C12 in various amounts,” Harman said.

C8, C10, and C12 are environmentally persistent man-made bioaccumulators called perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs). Studies have linked them to cancer, endocrine disruption, and reproductive and developmental problems in animals and humans.

Hartman’s student has presented the work at poster competitions, to the community, and in schools. “I’d like to see people listen to us. Everybody compliments it. They say, ‘Good job. Isn’t that terrible? Isn’t that too bad?’ It’s very difficult to fight the oil companies and convince people who are very poor—and some are now very rich—that they should stop participating in ‘the oil spill’ as I call it.”

Despite that, Hartman said his students remain adamant and impassioned. Three graduates work in North Dakota’s Game and Fish Department, and one went on to work for an oil company as its environmental specialist.

“(The company) has new devices on their flares oxidizing 99 percent of their materials. She makes them leak-free. She’s very passionate,” Hartman said.

• • •

On the Navajo Nation, Charley is working to infuse science into policy decisions, too, quietly sorting through the lingering aftermath of the “manmade technological disaster” that uranium mining has left in its wake. “Eventually I may publish, but I’m just a scientist. I’m not here to gather fame,” he said.

Instead, he shares his insights from years of research with people who have a direct vote in deciding how to handle the mess that remains.

Oliver Whaley, executive director of the Navajo Nation’s Environmental Protection Agency, is one of those policymakers. He takes a spiritual view of the current situation, referencing the Navajo word for “harmony.” By most standards, he said, “we’re considered an energy tribe, and we’ve exploited those resources. We’ve gotten a lot of revenue. If you go back in time, we probably should have never taken that uranium out of the earth. We’re finding now that there are physical, emotional, and social ways that we’re paying for it. If you live in accordance with what our teachings are, we wouldn’t have these issues. We shot ourselves in the foot.”

But can the wounds heal? As Charley prepares to monitor livestock, he said he feels that the Navajo people need monitoring, too—in ways that numbers can’t so easily quantify.

“Somebody has to look more deeply at the psycho-social impact, the families that see their loved ones die of these crippling diseases like cancer.” He wondered, “How do they equate it? How do they cope with it? How do they see the government that was entrusted with treaty rights and agreements to protect them? There’s a lot of resentment and mistrust.”

Charley lives with those questions, too. And while his family’s history may have sparked his line of research, it’s ultimately a hope for the future that keeps him going.

Katie Scarlett Brandt is a freelance writer based in Chicago and a frequent contributor to Native Science Report.