The long history and hopeful future of Mohawk language revitalization is explored in a new report

By Paul Boyer

Native language revitalization is often said to be a young movement. While nearly all of the nation’s indigenous languages are threatened, and dozens are now characterized as “dormant,” many tribes and Native communities are only now taking steps to reverse the loss.

On the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation, however, language survival has been a priority for decades. Carole Ross, who grew up on the reservation and now teaches the language, recalls that, as a child in the 1950s, Mohawk was both widely spoken and actively protected. “When you come in this house,” her father once said, “you speak Mohawk.”

With an estimated population of 14,000, the Mohawk nation (known as Akwesasne), straddles the St. Lawrence River and includes territory in both New York and Canada. Despite its small size and fragmented boundaries, however, the reservation now supports two well-established immersion schools, numerous adult instruction programs,and policies that promote use of Mohawk throughout the community. Mohawk linguists and language teachers travel the country, serving as speakers and consultants.

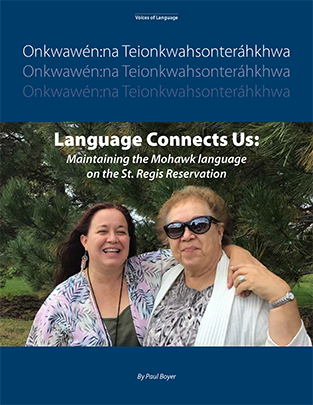

How the tribe developed this expertise, and what it means for the future of the Mohawk language, is the subject of Language Connects Us: Maintaining the Mohawk language on the St. Regis Reservation, a new report from Native Science Report Press.

In later years, a second immersion school was also founded on the Canadian side of the border and a diverse variety of adult education programs were established. As part of this work, the tribe pioneered use of computer-based instruction and, in recent years, also supported an innovative language and culture apprenticeship program. Adult students, studying full time, learned traditional skills—such a strapping and gardening—by working with elders in the morning. Afternoons were reserved for formal language instruction.

The 30-page report (available here) examines the social and political forces that led to the founding in 1979 of the Akwesasne Freedom School, one of the nation’s oldest Native language immersion schools. Although small and chronically underfunded,the school was one of the first to teach academic subjects in a Native language. Today, all subjects in grades k-9 are taught in Mohawk.

These and other programs make the tribe a leader in the nation’s emerging language revitalization movement. At the same time, the report documents concern that language fluency is eroding despite this work. More than 500 tribal members are said to be fluent speakers, but most are older. Language advocates note that while children and adults are studying Mohawk, the language is not yet being reintroduced into the home. As linguist and instructor Dorothy Lazore noted, Mohawk remains “a school language,” not the language of daily life.

How the language can move from school to home and community remains an open question, though Carole Ross believed much depends on leadership from the tribal government. It is a hopeful sign that the tribe, which has long supported language instruction for tribal employees, is currently developing its own language certification program, with a goal of producing a cadre of fluent speakers who will continue as teachers.

Native language advocates are often challenged to defend the value of their work. Why teach a language that few will ever speak? On the Mohawk reservation, teachers and community activists have ready replies. For Carole Ross, Mohawk helps build a sense of identity and common purpose in what all agree is a politically and geographically fragmented community. “With all of the imposed borders and jurisdictions, the one thing that always connected us here in Akwesasne was our language,” she said.

In this view, the Mohawk language is neither antiquated, nor isolating. Rather, it both heals and builds bridges.

Taking Back the Language is published by Native Science Report Press as part of its Voices of Language project, a new initiative examining how Native communities in the Americas are working to sustain and revitalize their threatened indigenous languages. Funded by the National Science Foundation, Voices of Language focuses on the work of individual educators and activists. By telling their stories, the project hopes to provide inspiration and insight to others taking part in this young movement.

The full report is available for free download. Print copies are available, as well. A limited number are available without cost to tribal and other organizations working on language revitalization issues. For more information about individual and bulk orders, please contact Native Science Report.

Paul Boyer is editor of Native Science Report