On the twenty-fifth anniversary of their designation as land grant institutions, tribal colleges are working to strengthen relationships with their mainstream university partners.

Story and photos by Melanie Lenart

Extension professionals from 21 tribal colleges and universities mingled with representatives from ten state land grant universities at a late October event in Denver designed to inspire collaboration. The activity preceded the annual First American Land Grant Consortium (FALCON) conference, which also highlighted the twenty-fifth anniversary of the legislation that gave tribally controlled colleges land grant status.

After giving the opening blessing, Latonna Old Elk of Little Big Horn College in Montana likened the tribal colleges and universities to a “stepchild” in the Land Grant system because of the relative lack of resources available to the TCUs.

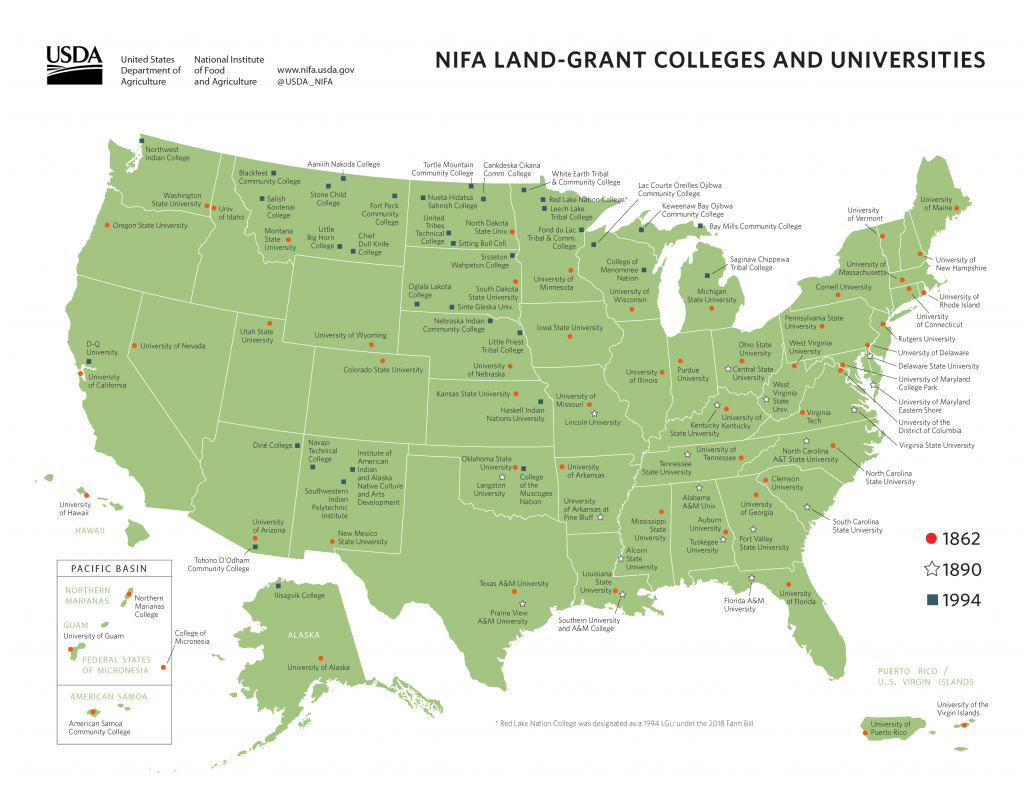

“Some families embrace the stepchild, but others don’t,” she clarified later to a smaller group at one of the tables set up to facilitate conversation among professionals from the tribal colleges during the pre-conference event highlighting collaboration among the two different types of land grant institutions. Congress added tribally controlled colleges to the list of land grant institutions in 1994. Although they are the youngest members of the land grant community—the roster includes both large state universities, numerous historically black colleges, as well as several elite private institutions, such as Cornell and MIT—the so-called “1994s” have a similar mandate to share knowledge and expertise with the local population through extension programs.

This mandate was first established in 1862, when the federal government financed the first land grant institutions by handing over large tracts of land to designated colleges or universities in every state, with the provision that income from the sale or use of the land would support the development of agriculture and extension programs.

Over the past 150 years, most of the original “1862” institutions have grown into major public universities and their extension activities have expanded to encompass a variety of programs, including personal finances, substance abuse prevention, and 4H youth activities, alongside the outreach efforts for raising livestock and growing crops. Federal funding continues to support these and other programs.

Of course, the land ceded by the federal government to the 1862 land grant institutions wasn’t really theirs to give, as the institutions are starting to acknowledge. At the conference, Ashley Stokes of nearby Colorado State University shared a video clip showing CSU employees and members of local tribes acknowledge that the nearby land developed by the university is on the traditional homeland of the Arapaho, Cheyenne and Ute. The video, which is expected to be posted on Colorado State’s website, seems to be part of a trend for land grant institutions to acknowledge their roots on lands occupied by tribes.

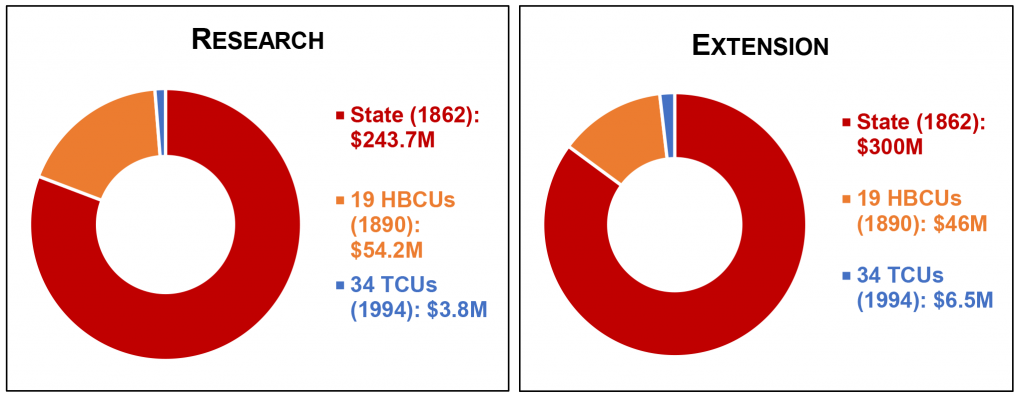

For instance, a statewide Cooperative Extension event hosted in Tucson by the University of Arizona featured blessings and performances by members of the Tohono O’odham tribe, whose homeland was ceded to develop the college. The O’odham continue to live on some of their ancestral land further southwest of this major city and last year celebrated the twentieth anniversary of their own tribally controlled college, Tohono O’odham Community College. Yet not all land grant institutions are extending olive branches to local tribal colleges. Comments made during the round table discussions supported Old Elk’s interpretation of the unequal relationship between the “1994s” and “1862s.” For example, while funding for 1862 state extension programs typically registers in the millions, funding for TCUs usually reaches tens to hundreds of thousands.

Several workshop participants, talking in a breakout group, said they had never met an 1862 representative from their state, or that they didn’t even realize they could collaborate with them on projects. Others reported that they often heard from the 1862s in their states at the last minute with requests to join grant proposals; some suspected their colleagues were just seeking the points provided in review for collaborating with a minority-serving institution.

This inspired Charlie Stoltenow of North Dakota State University to point out that the 1862 institutions are supposed to provide programming to a cross-section of their statewide constituents—and they have to prove it during civil rights reviews every decade, giving TCUs leverage when decisions about funding and program development are being made.

Because most tribal colleges are small institutions and have limited resources, many TCU extension programs amount to a “one-person show,” representatives agreed, so they generally welcomed the concept of more assistance from 1862s who were willing to help support the efforts deemed important by tribal college colleagues.

When encouraged by an 1862 colleague to “start knocking on the doors” of the 1862 land grant universities, Amanda Sialofi of Ilisagvik College in northern Alaska quipped, “We’re not knocking, we’ll kick the door down.” Still, like many of the TCU representatives at the meeting, Sialofi acknowledged that distance can be as big an issue as indifference. In her case, a visit to her state’s 1862 would require a plane trip.

Benita Litson, land grant director for Diné College, noted the Navajo Reservation she serves stretches across three states: Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. Her extension team collaborates with land grant institutions in all three states and even nearby Colorado. Diné College was the first tribally controlled TCU, and Stokes recognized Litson and the college for extensive success at collaborations.

When asked later about the collaborations with 1862s, Litson responded, “It’s not easy. We’re learning along the way who our true partners are. By true partners, I mean people who are reciprocating with information, back and forth.”

For instance, she explained that some collaborating universities insist on sending their own people to do trainings, such as in food safety, while others are willing to “train the trainers” and then allow Diné’s extension program to provide certification to their clients. Similarly, one institution will share programs readily and make them available for adapting while another will restrict them.

Challenges in jurisdictions can be a big issue along with the large distances involved. Even something small like requiring participants to register for a program online, as some do, can hamper program success because some potential participants lack internet connections.

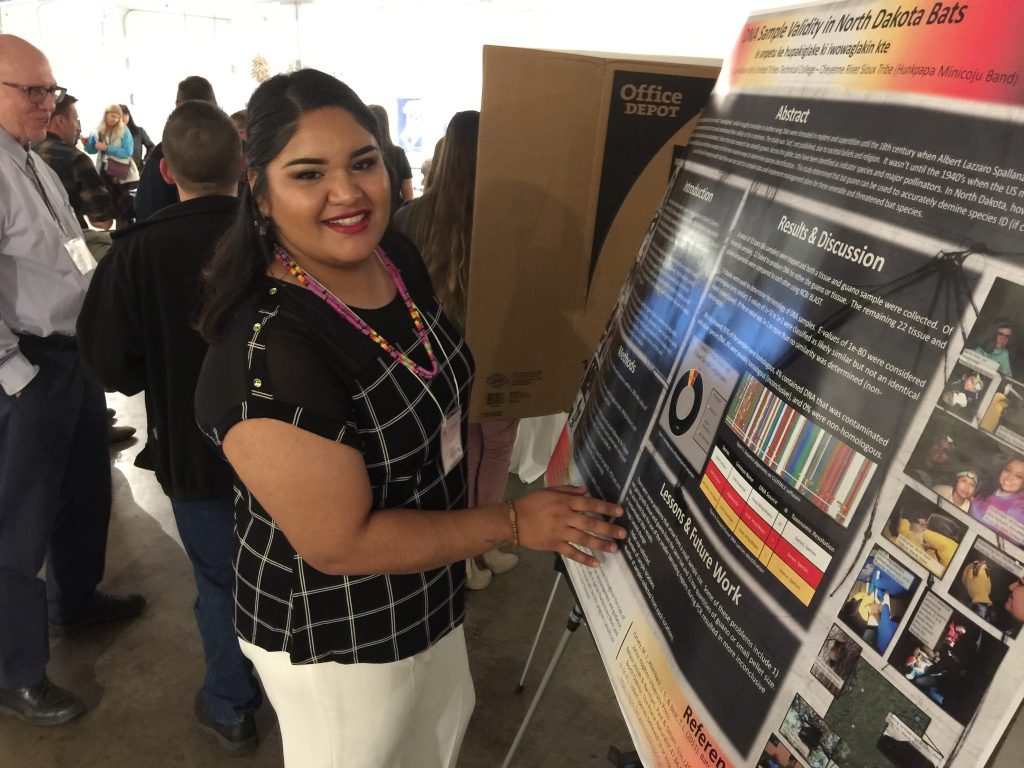

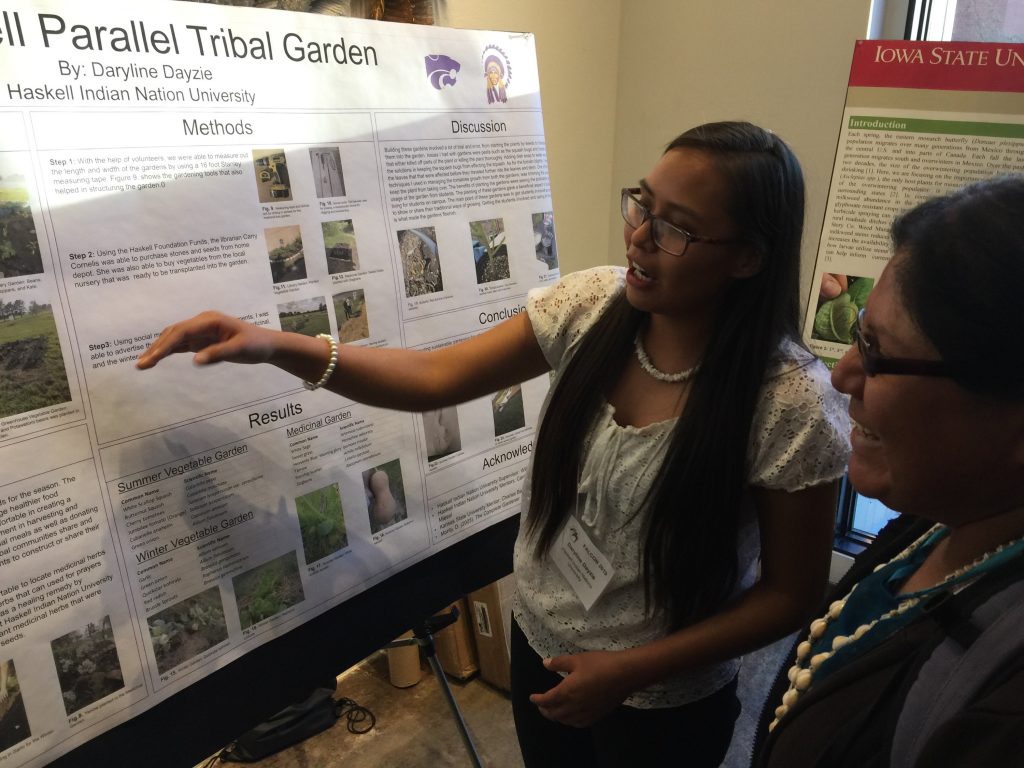

Many workshop participants agreed that success or failure of an attempted collaboration often comes down to individual agents or researchers. Years or decades of collaboration can fade away when a longtime extension agent at an 1862 institution is replaced by someone with less interest in the project. Despite the many challenges, some state institutions do a tremendous job of working with local TCUs, sometimes sharing their labs and expertise as well as research dollars. Signs of collaboration showed up in logos displayed on the posters of TCU students describing their research projects, and in the talks given by students and faculty during the FALCON workshop itself.

One student, Korrie Johnnie of Diné College, reported on her work in a collaborative project to enhance the quality of sheep wool, meat, and markets for local producers. The college partners with Utah State University to analyze select wool fibers and carcasses as provided by ten Diné sheep producers who volunteered to participate in the study. The study demonstrated an improvement in the quality of the wool following the introduction of a South African Meat Merino ram at the beginning of the three-year study. Partly because it focused on an issue valued by the community, the collaboration was considered a success. (A list of specific strategies for successful collaboration is included below.)

The theme of partnership carried through the conference. Carrie Billy, president and CEO of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, described the work she and others had done to get the 1994 legislation passed to support tribal colleges under the auspices of the Land Grant mission. Many people had opposed the concept initially, including a few from the existing federally supported TCUs.

“It really made us focus on developing strong partnerships with people we’d never worked with before,” Billy said. She described working with Republicans, who had control of both the House and the Senate during this time frame, to get the tribal college legislation through. As with collaborations, building relationships is key, she noted. For instance, Sen. Jeff Bingaman (D-NM) provided crucial help by including the legislation a rider. With his encouragement and support from other members of the House and Senate, many of them from the other side of the aisle, “we put it on a bill that had to pass both the House and Senate, as part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act.”

Billy commended longtime FALCON Director John Phillips, noting that he has been working to support TCUs almost from the beginning. He started with tribal colleges in 1997 as extension director of Cheyenne River Community College, then worked with AIHEC to help integrate TCUs in the Department of Agriculture in 2000 before taking the role of FALCON director in 2004.

Phillips and others on a task force formed at the meeting will work to provide additional opportunities for networking and collaboration between 1994s and 1862s in the near future, he promised in his closing comments of the collaboration workshop.

While improved collaboration has been a goal since the legislation passed 25 years ago, the effort started gaining steam about three years ago during a meeting in Wyoming, he said. FALCON will be working with others to identify future meetings that could include the collaboration discussion to maintain the forward movement.

“We want to honor your commitment for being here today by making sure something happens,” Phillips assured the group.

Advice from TCUs to hopeful collaborators

Here is some advice drawn from the discussions among representatives of land grant colleges, with a focus on recommendations given by the TCUs—“1994s” in the extension context—to those with four-year universities, especially those geared for extension efforts in communities.

- Successful collaboration requires building relationships among people.

- Building relationship takes time. It’s best to have an ally in the community to get started.

- Ideally, come in with a team that has had experience in working with tribes.

- “Show your face” to build relationships, including being part of community events that might not fit into the scope of your project.

- Attend or hold community meetings; even if you think you know what needs to be done, you need to do this to build interest and educate the community about the project.

- Listen to understand, not just to check off a box.

- Work on topics and issues initiated by the 1994. Be a partner on existing programs or programs sought by the 1994.

- Include the 1994 at the table from the beginning when writing grant proposals.

- The hopeful partner should ask, “How can we work together?” rather than say, “Here is what we can offer you.”

- Provide opportunities for 1994 students to do internships at the larger institutions.

- Keep in mind that most 1994s focus on teaching, so time to travel is often limited.

- Stay neutral regarding local issues, acknowledging that the tribe’s issues are not your issues.

- Recognize that tribes usually have a more horizontal, inclusive approach than the top-down hierarchy typical of many western institutions.

- Understand that 1994s are generally operating with staff shortages. Spending time to help out with programs can be as or more welcome than providing funding.

- Meet with neighboring Extension agents to hear about their mistakes and successes.

- Blessing and ceremonies are important to tribes. For meetings, consider paying an elder from the community as a consultant to lead these sacred activities in a culturally appropriate way.

More photos from the 2019 FALCON Conference

Melanie Lenart, Ph.D., is a scientist and writer who spent more than a decade of her postdoctoral career with the University of Arizona before joining the faculty as a science and agriculture instructor at Tohono O’odham Community College in 2015.

This article involves the interpretation of the author and does not reflect the views of Tohono O’odham Community College.