Dr. Costello Brown worked to advance educational opportunity for minorities during his long tenure at the National Science Foundation. In a new memoir, he writes about his family’s experiences with slavery and the importance of education in his own life.

By Carty Monette

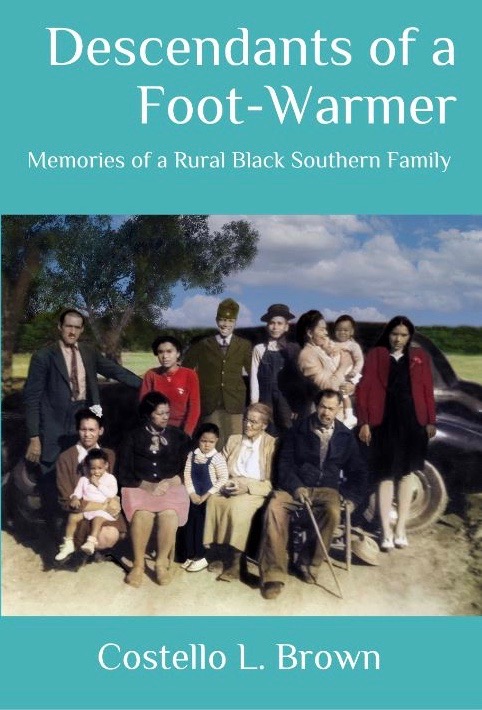

Descendants of a Foot-Warmer by Costello Brown is titled after the first job given to a slave named “Queen,” the author’s maternal great-great grandmother. In the 1840s, or earlier, Queen was taken from Sierra Leon, a country on the southwest coast of West Africa, and brought to America. Just seven years old, she was put to work as a “foot warmer” –a slave who warmed the feet of the slave master by sleeping at the end of his bed. The story of Queen serves as the beginning of this enticing memoir, which highlights the challenges and obstacles that poor and disadvantaged Black Americans encountered in pursuit of survival and, more specifically, of education.

The stories cover approximately 175 years of multi-generational family history. They elucidate the diligent skills that have guided the Brown family as slaves, as sharecroppers, and as landowners, leading up to their present-day accomplishments. Full of humor and wisdom, each story reveals both joy and hardships. Chapters featuring Christmas gatherings emphasize how critical the holiday was, and is, to preserving multi-generational family connections and traditions.

The author acknowledges that, although they were poor, they did not know they were poor. Family sheltered the three siblings. At one point in the narrative Costello muses whether the very young Brown siblings “even knew that we were black or clearly had no understanding of being black in the South at that period of time.” Exposure to white people was protected by family and the other black people who populated The Sweet Gum neighborhood of Caswell County in North Carolina “even though,” Brown writes, “the Ku Klux Klan held their regular meetings less than five miles from our home.” After slavery many freed slaves stayed around the plantations where they had been held as slaves. They became sharecroppers who worked the land for the landowner. As the story unfolds we learn Costello’s maternal great-grandfather managed to buy a small plot of land. He passed away before paying for it. The maternal grandfather, by hard work and resourcefulness, was able to pay off the debt. Ownership was a turning point. The family reaped the benefits of working their own land instead of generating the wealth of white landowners.

Ownership had another positive result. Christmas dinner at the home of Brown’s grandmother to this day takes place on that same plot of land where the author’s ancestors worked as slaves and near where Queen was brought as a seven-year-old slave girl. Each year family still gather to share good food, family recipes, and to retell stories of the past.

From this web of stories education emerges as a primary theme. Costello’s mother made clear how important education was. She warned her children, “Unless you want to be a foot-warmer, you had better go to school and get an education.” When state colleges were still segregated, his mother earned a teacher diploma from a Historically Black College and University (HBCU). She taught in segregated k-12 schools.

Like his mother, Costello’s academic journey began when he enrolled and graduated from a HBCU. Several Brown family professionals are HBCU graduates and, like Costello, many subsequently earned advanced degrees from acclaimed universities. Several, including Costello’s children, have emerged as leading professionals. Some of their stories are included in the book.

We learn of the author’s commitment to facilitate access and success to educational opportunity for underserved populations. From the mid 1990s to early 2000s Costello served as a division director at the National Science Foundation. He was charged with promoting systemic change in K-12 math and science education at primarily Black serving schools. An added value was his work with tribal colleges. During this period NSF implemented the Tribal College Rural Systemic Initiative (RSI). The program provided the funds to lead systemic approaches to improve K-12 STEM education in 109 schools located in six states on 20 Indian reservations. For tribal colleges and Indian people, RSI was a beginning to new opportunity. Currently, after more then 25 years, NSF has funded millions to tribal colleges for STEM capacity building through program’s like the Tribal Colleges and Universities Program (TCUP) initiated in 2000.

Since retiring, Costello has consulted for Quality Education for Minorities (QEM). Tribal college and university administrators and STEM faculty will recall his presentations during TCUP Leaders’ Forums and special workshops where he continues to serve as a consultant to tribal colleges for Sisseton Wahpeton College and to QEM.

Brown explained that his book began as a series of short stories written for his grandchildren so they would know their grandfather, the Brown family history, and family traditions. The stories evolved into a book that in over thirteen chapters chronicles the joy and the pain of being Black and of being a Black family in America. Resiliency of the Brown family, beginning with that seven-year old enslaved “foot-warmer” has led to many extraordinary achievements.

• • •

Dr. Carty Monette, served for 30 years as president of Turtle Mountain Community College on the Turtle Mountain Reservation of North Dakota until his retirement in 2005. Since then, he has worked as a project director at the National Science Foundation for the Tribal Colleges and Universities Program, and as a senior advisor with the Quality Education for Minorities Network. Monette also helped establish the Tribal Nations Research Group, where he now serves on the board.

Published May 17, 2021

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications of new posts by email