In a region scarred by coal mining, a new research center at Chief Dull Knife College is helping the Northern Cheyenne Reservation of Montana remain an environmental oasis.

By Melanie Lenart

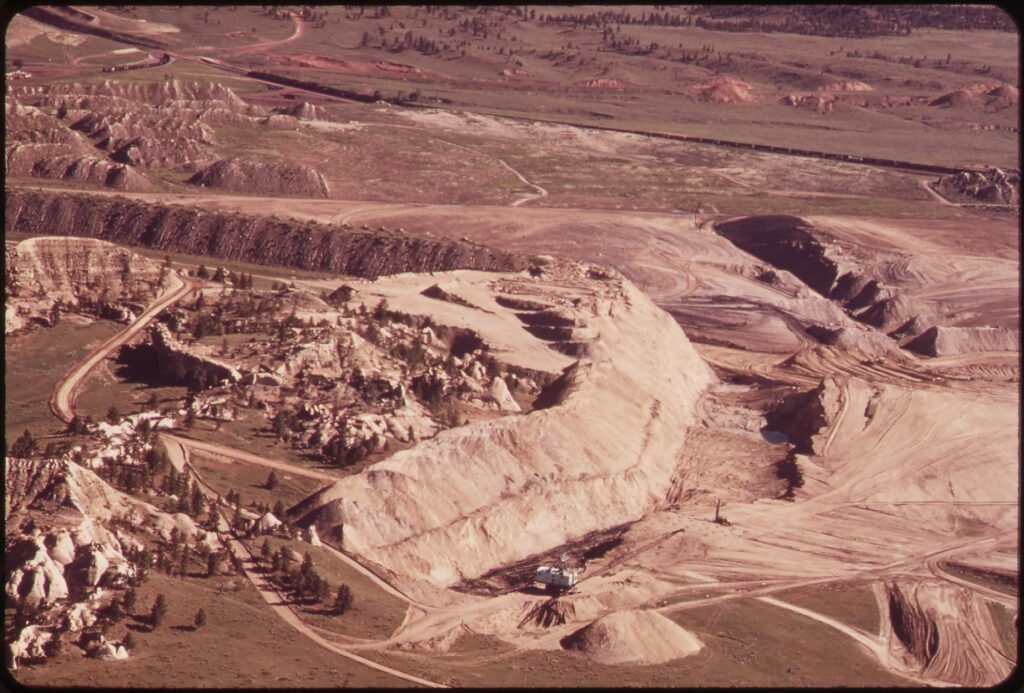

The Northern Cheyenne have long resisted joining in the coal mining that has torn up the land surrounding their reservation in southeastern Montana, as well as the coalbed methane extraction that has taken hold more recently. Members of the tribal nation instead focus on protecting their land and water, including from off-reservation mining practices.

In 1977, the tribal nation adopted air pollution standards more stringent than the US the Environmental Protection Agency’s national standards. Among other outcomes, this forced a nearby coal-fueled power plant to scrub contaminants from its emissions. In 2015, the Northern Cheyennes’ efforts to adopt more stringent water standards beat out court challenges from nearby industrial giants. Among other things, the rules restricted how much salty water the methane drilling companies could release into the Tongue River—which serves as the eastern border of the reservation and divides Montana from Wyoming.

Now Chief Dull Knife College has established a new research center that will strengthen the tribe’s capacity to monitor the reservation’s waterways and also provide clean water for residents. Supported by a $4.2 million National Science Foundation grant, the college’s newly established Environmental Research Center is also working to attract more students into STEM pathways.

Jeff Hooker, principal investigator of the NSF grant awarded to the college in 2019, said the center is already helping to increase student retention.

“For those who have been our interns in our internship program, we have about a 74 percent graduation rate,” he said. “That’s telltale for the kind of impact we’re having.”

The graduation rate for the associate degrees offered by the college is roughly double or triple the typical 27 to 41 percent graduation rate for students seeking degrees at tribal colleges and universities, as cited in a May 2021 Department of Commerce report.

Since the receipt of its first NSF Tribal Colleges and Universities Program (TCUP) grant in 2002, faculty members have tried different tactics to see what seemed to work best to attract their students to STEM. After several other iterations, the college is working on a distinctly community-minded approach in its latest National Science Foundation grant, a TCU Enterprise Advancement Center, also known as a TEA Center.

NSF offers TEA Center grants “to build on the capacity developed through prior TCUP support and apply expertise to collaborations with communities in the institution’s service area, or nationally.”

Chief Dull Knife College’s grant builds upon a series of ongoing partnerships that address issues relevant to the reservation. “The difference now, of course, with TEA Center is that we’re trying to more firmly embed that community link,” Hooker said. “That’s what establishing this Environmental Research Center is about.”

Bringing students into research

Plans for the center include hosting a laboratory for systematic water sampling by the 12 paid student interns hired annually as part of the grant. The grant covers weekly student intern pay for 10 hours during the semesters and 40 hours during summer. Non-STEM majors also can participate in the internships. For several students, the opportunity to take part in meaningful research transformed their feeling about STEM.

“It was pretty scary at first. But after a while, I got the hang of it,” said April Killsnight, who is still deciding her career path. She started her internship right out of high school, where she had been a dual enrollment student with the college. “I think it was a cool experience. We got to get out testing the waters, getting water samples and whatnot.”

“I thought it was interesting that we were the first ones to actually test the (waters of the) Tongue River Dam,” said Katherine Bartlett, who aims to get a degree in social work and run a food pantry. The off-reservation reservoir feeds water into the Tongue River, known as vetanoveo’he in the Cheyenne language. The group would generally leave for the Tongue River Reservoir research site on Tuesdays and return on Thursdays, they said. The students would stay in teepees, while participating faculty members stayed in the research trailer or in their own rigs or tents.

Hooker credits the longer stays for field work as effective in getting students to see faculty members in a friendlier light. “We have a different chemistry with them as well, having had that experience.”

Students also learned to be more comfortable around university faculty members—and a more diverse student body—during the week-long research project most of the student interns participated in at Montana State University in Bozeman. They stayed in the dorms and worked on projects alongside students from Historically Black Colleges and Universities as well as other tribally controlled colleges.

“It was something totally different. I’d never been to an actual university,” James Russette said. He’s now more interested in getting a bachelor’s degree rather than an associate’s in nursing. He also has a back-up plan to segue into cell biology if he doesn’t initially get accepted into the competitive nursing degree program at the University of Montana.

At the university, Russette and Raymond Limpy from Chief Dull Knife College worked with two students from Blackfeet Community College on a week-long research project on zebrafish. Zebrafish develop from embryos in three days. They tested some traditional knowledge shared by the Blackfeet that drinking mint tea can cause miscarriages. Their research supported this, Russette said, as they found that adding mint to the water interfered with zebrafish embryo development.

“When we went to Bozeman, doing the labs up there with the embryos made me a lot more confident,” said Limpy, who plans to study agriculture. “Before that, I was always kind of scared.”

Adrian Demontiney said his group tested the effects of melatonin on zebrafish embryo development, finding it slowed their growth. He talked to a psychology professor during the visit, which he said reinforced his interest in pursuing a psychology degree.

Hooker noted that half of the 12 students participating in the summer internship started this fall at four-year institutions, including the University of Montana.

Homing in on what works

Hooker said he hopes Chief Dull Knife College’s STEM program has landed on a good mix of local research and off-reservation activities with university professors and other partners.

In some of the earlier TCUP projects, students did STEM research far from the reservation, such as working on chickpea production in Mali. Evaluators found these student interns often did well as they pursued their bachelor’s degrees at off-reservation institutions, but many of them longed for research topics they could imagine doing in their own communities.

In a 2014 NSF grant known as an Instructional Capacity Excellence in TCUP Institutions (ICE-TI), interns worked on projects located on Northern Cheyenne tribal lands. While many appreciated the experience, Hooker explained, evaluations suggested that keeping it exclusively local resulted in students having less confidence in applying their skills beyond the reservation than did the international set of student interns.

A subsequent NASA opportunity known as Rock On! allowed students to participate off-site to conduct experiments on a rocket shot 24 miles into space. The successful competition involving numerous colleges and universities from around the country gave Chief Dull Knife College’s STEM program the “buzz” Hooker was seeking. Since then, the college has generally been able to fill the Rock On! slots (when the program is not derailed by the Covid 19 pandemic) as well as the student internships offered under the TEA Center grant.

Concerns about water quality

“Many tribal residents are subjected to inadequate or toxic water supplies,” Hooker noted in his TEA Center proposal. “In addition, tribal lands have been impacted by years of abuse by mineral extraction or other land uses which harm the environment and/or ecosystems.”

The Northern Cheyenne’s 444,000-acre reservation sits within the Powder River Basin energy development boundary—the source of about 40 percent of US coal. A major coal-fired plant known as Colstrip has an array of coal ash ponds just 14 miles from tribal lands. Just one of the areas holds enough ash waste to fill more than 2,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools, which the state’s Department of Environmental Quality reportedly linked to the release of 43,000 gallons of contaminated water per day. So far, there’s no indication that the tainted water has contaminated the tribally owned groundwater wells serving many of the approximately 6,000 Northern Cheyenne who live on the reservation. But the company agreed in 2019 to pay $1 million in fines for contaminating water near a Pennsylvania plant.

A 2006 graduate of Chief Dull Knife College, Chauncey Means, found arsenic levels exceeding water quality standards in Crazy Head Springs during his research at the University of Montana. In his 2010 thesis for a master’s degree in environmental science, he explained that Crazy Head Springs is culturally significant to the Northern Cheyenne Tribe. For one thing, it feeds Crazy Head Ponds, which tribal citizens use for fishing and swimming and also as a water source for livestock.

Aging water pipes also can allow contaminants, such as lead, to leach into drinking water. Many people remember how residents of Flint, Michigan, were drinking lead-contaminated city water. Montana experienced something similar recently, when tests in February of 2022 forced the closure of drinking fountains in 110 schools because of lead contamination. Until a change in law passed in 2020, Montana schools had been exempted from laws requiring water testing.

A non-profit group led by Jaden Smith provides the Northern Cheyenne with “water boxes” they can use to purify domestic water for distribution. The college houses one for community use in its cafeteria. Hooker said the college interns could bring purified water to residents who would have trouble getting it on their own.

“Maybe we would have interns deliver water to grandma because she can’t get out or doesn’t want to come down or whatever,” Hooker said. “And all we ask in exchange is we want you to turn on the faucet and we want to take a sample. It will be logged and that will become one of our data points.”

Hooker stressed the importance of having data on water quality from both the wells, which many residents use for themselves and for their cattle, and the reservoir that feeds into the Tongue River.

“If we don’t get a baseline now, when someone builds a feedlot upstream or someone dumps coalbed methane effluent water into the stream upstream from us, how will we know what effect it had on the biologic diversity in the river itself?” Hooker said.

He also feels good about arming so many tribal citizens and potential future leaders with knowledge on interpreting data. Such skills can help in a variety of careers—including those involving decision making for the Northern Cheyenne Tribe.

“I love the idea that it started with research and looking at water resources on the reservation , and now it’s comefull circle so that we’re giving back to the community,” he said. “‘Research’ isn’t just an aspect of the college’s programs. It’s really affecting the community. And it’s affecting things that are real in your life.”

Melanie Lenart is a regular contributor to Native Science Report.

Story published December 5, 2022

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications.