Aaniiih Nakoda College’s Namibia Field Course explores connections, both cultural and ecological, between the West African nation and the Fort Belknap Reservation.

By Scott Friskics

In the pre-dawn darkness of their camp at the Uibasen-Twyfelfontein Community Conservancy campground in northwestern Namibia, students and faculty from Aaniiih Nakoda College slowly emerge from their tents. As they shuffle over to a sweet-smelling acacia-wood fire, they are greeted by hot cups of instant coffee and welcoming choruses of “Mwa lele po?” “Ya, ya, onawa. Mwa lele po?” “Onawa, onawa.” It’s the standard morning greeting in the Oshiwambo language: “How did you sleep?” “Yes, good. How did you sleep?” “Good, good.”

Waiting for the students at the campfire is Godwin Goamub, a game guard with the Uibasen-Twyfelfontein Conservancy. This morning, the students and faculty will accompany Godwin and his colleague Erlyn Touros on their regular patrol route – a 10-12-kilometer hike through acacia and shrub savannahs punctuated by striking inselbergs of red sandstone. Along the way, the group will be on the lookout for signs of elephants, giraffes, zebras, lions, cheetahs, and other wildlife that inhabit the area.

The game guards walk these routes several times each week and record wildlife sightings, as well as other noteworthy events, in little blue “Event Books.” Over the course of the year, Godwin’s and Erlyn’s Event Books and those of their fellow game guards will provide the conservancy with valuable data that the local community uses to inform strategies to reduce human-wildlife conflicts and to guide resource management and distribution decisions intended to benefit all conservancy members.

The whole process is about as low-tech, grassroots, and community-based as you can get, and it contrasts sharply with more top-down, technocratic approaches to conservation practiced in other parts of the world. To be sure, the community conservancy model is not without its problems, but it’s an alternative that is well worth learning about—and one that may hold particular relevance for wildlife managers on tribal lands in the U.S.

Today, students from ANC are getting a ground level view of how Namibia’s revolutionary community conservancy model works—and they’re hoping to see some of Africa’s legendary wild animals, too. In the end, they’ll have to settle for one giraffe sighting, an aardvark den, a snake-eating eagle, a horned adder, and lots of ungulate tracks—all while walking through an African landscape of timeless beauty.

Needless to say, the seven students and their four instructors from the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in north central Montana are a long way from home. According to Google, it’s 8,789 miles from Harlem, Montana to Twyfelfontein, Namibia. To get here, they flew well over 10,000 air miles (including two, 10-hour flights) and have endured miles and miles of jouncing along washboarded, potholed African backroads. It’s an arduous journey to say the least. Yet these students don’t seem to mind. Reflecting on her Namibia experience, one of the students, Amanda Lopez, put it this way, “It was definitely a once in a lifetime experience. I never thought I’d go that far from home. It was invaluable. I don’t think I’ll ever get that kind of experience again.”

The students traveled to Namibia for a 19-day field course titled, “Land and People of Namibia,” which is offered by Aaniiih Nakoda College through a grant from the National Science Foundation’s Tribal Colleges and Universities Program. According to Michael Kinsey, one of this year’s instructors, the Namibia field course is a unique opportunity for Aaniiih Nakoda College students to experience another culture, learn about the importance of rangeland management, and discuss similarities between the young west African country and the Fort Belknap Reservation.

“The trip allows students to experience traveling all over the world,” Kinsey said, “where many have never left the country, and experience new cultures and tell the story of the Aaniiih and Nakoda People of Fort Belknap.”

The field course is part of a larger project that offers students a continuum of integrated STEM learning experiences that begins with a pre-college summer academy, includes research opportunities and enrichment activities, and culminates with graduation from ANC’s B.S. degree program in Aaniiih Nakoda Ecology. Individual students, depending on their interests, may participate in one or all of these activities. The seven students enrolled in this year’s Namibia field course were a diverse group and included individuals majoring in Aaniiih Nakoda Ecology, Environmental Science, Computer Information Systems and Allied Health. In terms of their college experience, they ranged from first-year students to graduating seniors in the B.S. degree program. What they had in common was a desire—and the courage—to experience new things and learn about new places and different cultures.

To help them do that, the college teamed up with Mr. John Pallett, a Namibian naturalist and environmental scientist, who served as the course’s lead instructor. John’s deep and broad knowledge of his home country—not to mention his affable personality, excellent teaching skills, and rare ability to organize chaos—made him the perfect guide and instructor for the course.

In addition, this year’s students received the added bonus of being accompanied by four Namibian students from Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST). The Namibians are fourth-year students (“honors students”) concentrating in Nature Conservation and, in one case, GIS Technologies. Through casual conversations during long bus rides, shared meals, rock-climbing exploits, and late-night campfire sessions, ANC students and Namibian students shared stories and insights about their lives at home—whether that’s Fort Belknap or Oshakati. And, they become friends.

According to ANC student Shakayla Whitecow, “The Namibian students joining us for our trip was the absolute highlight of the entire trip. Interaction about wildlife, plants and landscapes and learning of the many cultures including each of their own, while teaching them about ours, is something I’ll always hold close to my heart and will never forget.”

Despite great distances and obvious differences, there are a number of similarities between Namibia and Montana; for starters, they’re both big, open, sparsely populated, and dry. Approximately the size of California, Namibia is home to about 2.6 million people who represent 14 different ethnic groups and speak 26 different languages. Its population density of 3.2 people/km2 is about the same as Montana (2.8). Most of the country receives less than 14 inches of rain a year (by comparison, Harlem averages 11.6 inches of precipitation per year), with places in the Namib Desert and along the Atlantic coast receiving an average of less than 2 inches of rain per year – and, in some years, none at all.

However, the connections between these two places run much deeper. Both Namibia and Montana – and, specifically, Fort Belknap – face a number of common environmental issues, and it’s these shared concerns that ANC students and faculty are here to explore. Examples of these common issues include the social and environmental impacts of hard rock mining (whether it’s copper, uranium or gold), endangered species management (whether it’s rhinos and cheetahs or black-footed ferrets and swift fox), human-wildlife conflicts (livestock predation, habitat encroachment, grazing competition between wildlife and commercial livestock), the pros and cons of industrial tourism and commercial trophy hunting, water scarcity and desertification in an era of rapid climate change, inequitable distribution of benefits from natural resource development – and, yes, dark histories of colonization and genocide, as well as the lingering legacy of systemic racism. It turns out that ANC students and Namibian students have a lot to talk about with – and to learn from – each other.

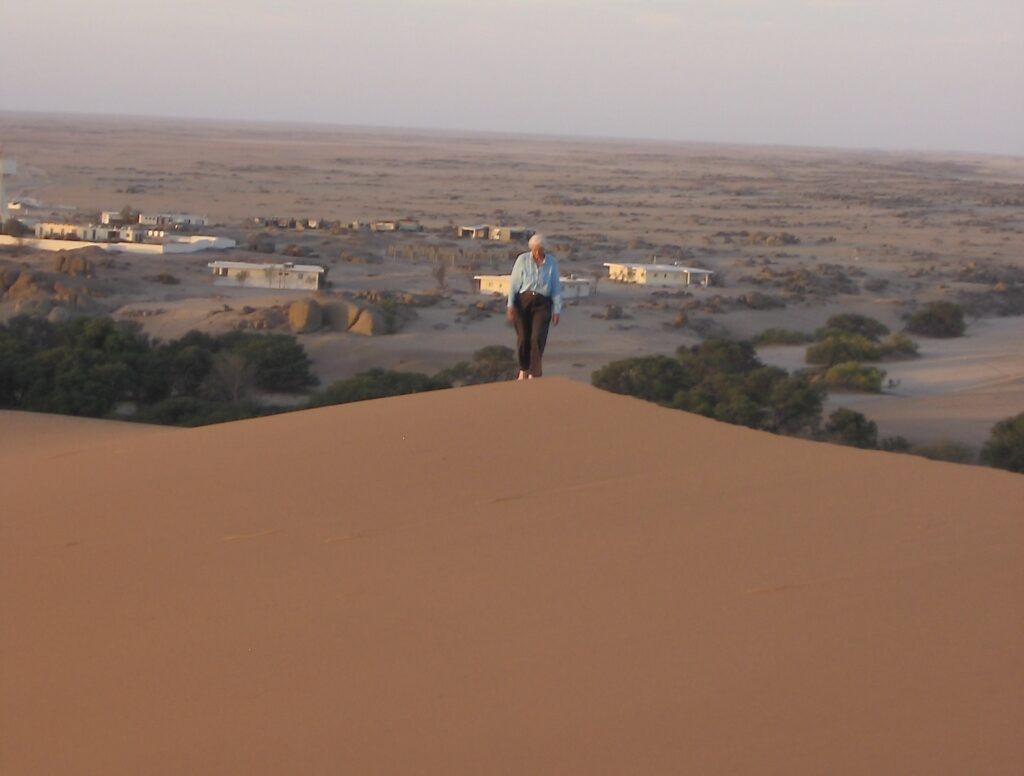

After more than two weeks in Namibia, the ANC students covered a lot of ground (roughly 2,000 km) and saw an amazing diversity of landscapes. Beginning and ending in the capital city of Windhoek, their route followed a large, clockwise loop through the center of Namibia. Along the way, they visited large, privately-owned farms (the “farmers” raise livestock, so we would call them ranches), the world-renowned Namib Desert Research Station at Gobabeb, the seaside resort town of Swakopmund, community conservancies at Uibasen-Twyfelfontein and King Nehale, Etosha National Park, and the Twyfelfontein World Heritage Site (famous for its 6,000-year-old rock art engravings). Upon returning to Windhoek, they wraped up their visit with a private meeting with high-ranking officials from Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, where the students shareed their experiences, asked their unanswered questions, and, as representatives of one sovereign nation meeting another, presented the ministry with a flag of the Fort Belknap Indian Community.

One of the common themes woven throughout students’ travels across Namibia is range management. At five different sites along the way, students perform rapid rangeland assessments—clipping vegetation from one-meter quadrants, weighing samples, and calculating carrying capacity and stocking rates. Results vary widely from site to site based on land use practices, grazing pressure, and precipitation. It’s a quick and dirty method, but the findings, along with a visual assessment of site conditions using a simple scoring rubric for six rangeland characteristics, offer insights into the sites’ overall condition and their capacity to support livestock and wildlife grazing. Photo points and GPS readings are taken at each site, and results are compared with previous years’ findings (This is the third time ANC has offered the course in Namibia; the first since COVID). Results are also shared with the landowner/manager at each location, so that the information can be used to inform their management decisions and grazing practices.

It’s fair to ask the question: Why Namibia? Why travel thousands of miles to study African rangelands, human-wildlife interactions, and conservation practices? Couldn’t the students learn these things back home?

The easy answer is that they do learn some of these things back home; it’s not an either/or proposition. Prior to going to Namibia, students perform the same assessments in Fort Belknap’s 29,000-acre Snake Butte buffalo range. Some also participate in much more comprehensive rangeland assessments being conducted by the Fort Belknap Buffalo Program, in collaboration with partners from the World Wildlife Fund and Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. Regardless of the method or location, students are confronting the same basic questions: How many buffalo/cattle/sheep/wild ungulates can the land support? How do we practice responsible and sustainable land management for the mutual benefit of the soil, plants, animals and people? Namibia is a great place to go to wrestle with these questions. Only 33 years old (Namibia gained its independence in 1990), Namibia is a young country deeply committed to the just, equitable and sustainable caretaking of its natural resources. Consider this passage from Article 95 of Namibia’s constitution: “The state shall actively promote and maintain the welfare of the people by adopting … policies aimed at the maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological processes and biodiversity of Namibia and utilization of living natural resources on a sustainable basis for the benefit of all Namibians, both present and future.” There is much to be learned from a nation that talks about ecological processes, biodiversity, and sustainability in its constitution. And it’s more than just words. Approximately 47 percent of Namibia’s total land base is under some form of protective designation, whether it’s a national park, UNESCO World Heritage Site, Ramsar wetland, state protected area, or community conservancy.

Beyond all that, there’s also the human connection between Namibia and Fort Belknap—and that human connection is Dr. Liz McClain. Liz arrived as an instructor at Aaniiih Nakoda College (then Fort Belknap College) back in 1995, after spending the previous 15 years teaching and conducting research in Namibia. An insect physiologist by training, Liz spent many of those years at the Desert Research Station at Gobabeb studying, among other things, behavioral and physiological mechanisms that certain desert beetles use to “beat the heat.” She was a faculty member at the University of Namibia—and an active member of the faculty union—during the liberation struggle of the late 1980s that ultimately led to Namibia’s independence on March 20, 1990. But Liz is much more than a scholar and activist; she’s a people magnet. Her infectious kindness, good-humor, and generosity draw everyone around her into her circle of friendship. Throughout her time in Namibia, Liz put down deep roots and established lasting relationships with her faculty colleagues, her fellow researchers, her former students (many of whom now hold leadership positions in the Namibian government), her Oshiwambo and Topnaar families, and so many others. It’s this network of enduring relationships that Liz decided to tap into to make this singular learning experience possible for ANC students and faculty, 27 of whom (21 students and 6 instructors) have now participated in the field course since 2018.

Among education researchers, international learning experiences usually appear at or near the top of the list of “high impact practices” that contribute to student retention, graduation, and academic success. That certainly holds true for Aaniiih Nakoda College’s Namibia field course. Among the 14 students who participated in 2018 and 2019, consider these numbers: One hundred percent returned to college for the fall semester following the Namibia summer course; 93 percent have earned an A.S. degree; and 57 percent have earned a bachelor’s degree (with another 21percent currently enrolled in a B.S. degree-granting program). Two have gone on to graduate school, while others are doing internships with Smithsonian or working for the Fort Belknap Fish & Wildlife Department, Fort Belknap Environmental Protection Office, White Clay Immersion School, Life’s Language Lodge, and elsewhere.

As the Scottish philosopher David Hume pointed out, connecting the dots between cause and effect is a tricky proposition. However, this much seems clear: Traveling to Namibia and participating in the Namibia field course has had a positive and lasting – transformative – impact on the lives of these ANC students. While the participant tracking data provide one way to make that argument, a much more compelling case can be made by listening to what the students themselves have to say about their experience.

For Sage Lone Bear, “It gave me a bigger lens for thinking about conservation and caring for the environment. It’s a big deal in Namibia; here, it doesn’t seem so serious. I feel we have way more resources that we take for granted. I honestly am humbled and feel more appreciative. With the African students, I saw that they are very dedicated to their culture and heritage, and it made me more motivated to learn my own culture and heritage.”

As for Shakayla Whitecow, “The trip encouraged me to be more present in my own culture and making it a priority to learn our languages. Namibia impacted my life in the most positive way, and I couldn’t be more grateful.”

• • •

Scott Friskics is director of sponsored programs at Aaniiih Nakoda College.

Story published September 7, 2023

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications.