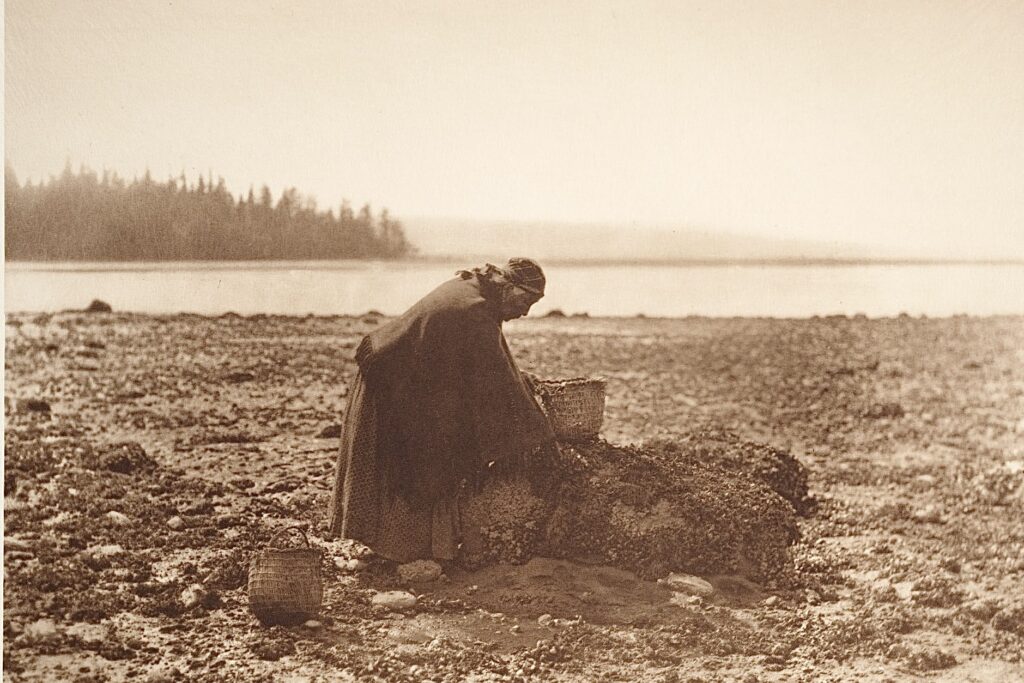

Native Alaskans are at greater risk of deadly shellfish poisoning. In response, tribes are running their own testing program. A new study examines the outcomes.

By the Native Science Report staff

Shellfish harvesting has sustained Alaska tribes for generations. But a recent study found this long-standing tradition is eroding as algal blooms—some of them carrying a deadly toxin that don’t kill shellfish but can be fatal to those who eat them—extend beyond summer.

The Sitka Tribe of Alaska collaborated with researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the University of California-San Francisco to conduct the research study, which involved interviewing 27 people involved in harvesting shellfish and testing for the toxin.

All commercial harvesters must test for these toxins in shellfish such as clams and mollusks. However, shellfish harvested for non-commercial use is not tested, putting Native Alaskans who rely on subsistence foods at greater risk. Fifty-three percent of cases of poisoning by the toxin involved Alaskan Natives, more than three times what would be expected based on their population alone. The toxin causing paralytic shellfish poisoning can cause dizziness, vomiting nausea, temporary paralysis and even death.

“Due to climate change, their traditional knowledge isn’t helping them out anymore,” a study participant told researchers. “People were getting sick, people were dying, and the vast majority of the people that were dying and are getting sick were tribal.”

This situation led several Alaskan tribes to create a network to test shellfish from subsistence harvesting sites across southeastern Alaska. However, spottiness of testing, and its complete absence during the pandemic, has led to confusion, according to the research published in GeoHealth. “You have polar opposites in this region, of people who heavily rely on it, and other people that will not touch it anymore because they are afraid or haven’t ever done it,” a study participant said.

About four out of five of those interviewed viewed testing as important for health and safety of the community. All study participants were reported only as a number.

“I grew up harvesting clams as a child. We would go dig butter clams and then we’d have a big clam bake, and it was a lot of fun and it was great,” another participant explained. “We want people to take their children out to go clam digging and enjoy eating a food that is good for them that they can also easily harvest themselves.”

About half the study participants said fear of paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSPs) has discouraged shellfish harvesting, to the point where many coastal residents are not even introducing their children to the practice. This removes an important local food source for subsistence harvesters and leads to cultural loss, which can affect people’s mental health.

“If you think about having this tradition that you’ve practiced in your family for generations now being lost, that really has an impact on someone’s health and wellbeing,” a participant explained.

Study participants stressed the importance of risk communication that explains the benefits of harvesting but balances it with information such as species-specific warnings at relevant times and places. Instead, distrust in the continuity of testing has followed a shut-down in testing during the pandemic. During Covid isolation, officials recommended avoiding shellfish harvesting altogether. Participants said this had a negative impact on this traditional practice.

Even now, efforts to test for the toxin remain hampered by overextended staff, vehicle and boat availability, and poor roads to many sites. Even when testing occurs, it may take a week or more for harvesters to receive results.

Meanwhile, participants reported that the window of exposure to the toxin causing paralytic shellfish poisoning from a seasonal risk during spring and summer to a year-round risk, thanks to increasing temperatures in coastal Alaskan waters and pollution that feeds algal blooms.

“There certainly is a trend toward having a longer season where PSPs are accumulating in shellfish,” a participant said. “And so, there’s harmful algal blooms happening earlier. And then they are more intense, and they are lasting longer.”

Study authors indicated they may expand the research on subsistence shellfish harvesting to include more individuals from smaller, remote communities who may be especially susceptible to toxin exposures. The study was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Story published April 4, 2024

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications.