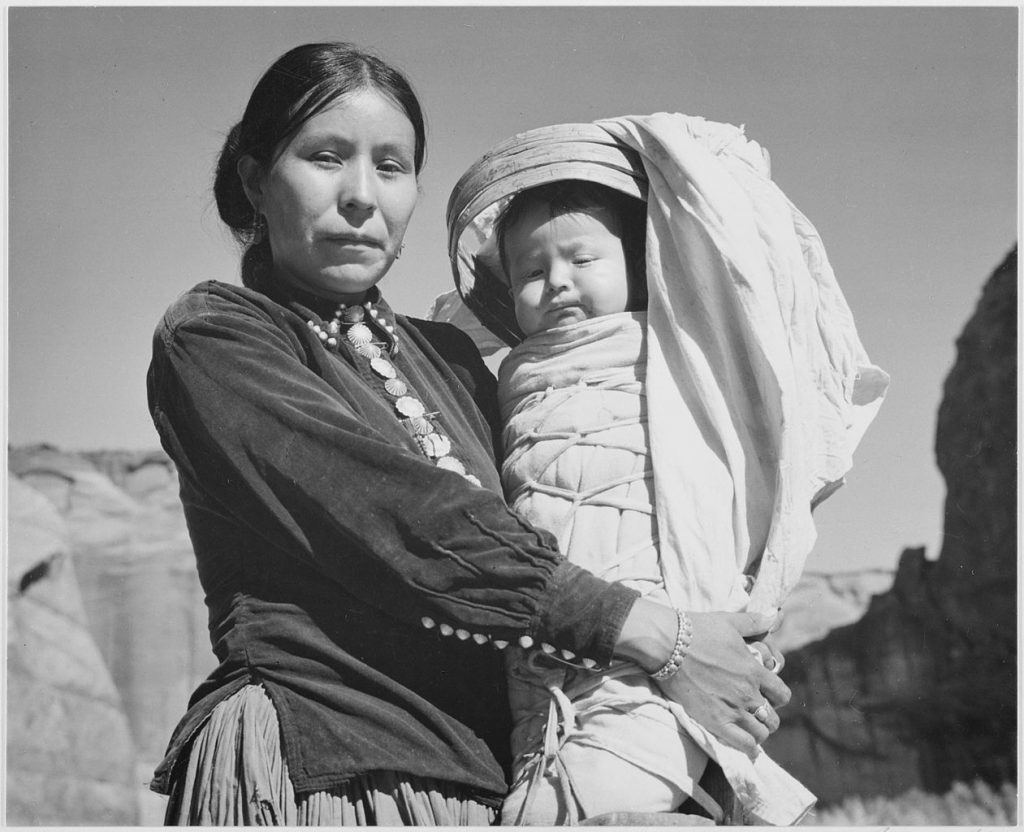

Working in traumatized communities, tribal colleges and their STEM faculty do more than educate students; they also help build stronger nations.

By Paul Boyer

Native Science Report recently published a video, produced by the National Science Foundation in 2009, documenting the growth of STEM within tribal colleges. While many students, faculty, and administrators spoke about the value of science and the quality of the colleges’ STEM programs, I was particularly struck by the words of Arnold Clifford, a Navajo botanist working with students at Diné College.

Standing against an expansive backdrop of sagebrush, he referred to the land around him as a “natural laboratory.” And while the Navajo peoples’ connection to this land is deep and ancient, Clifford said it is, in many ways, still waiting to be explored. “Just about everything out here hasn’t been studied yet,” he said.

Many Americans view reservations as isolated and impoverished regions, far removed from the main current of the nation’s economic and intellectual life. Because most tribal colleges are located on reservations, they are similarly imagined to be marginalized institutions, held back by their rural settings, limited resources, and, for faculty, limited opportunities for scholarship and professional growth.

But it was obvious that Clifford did not feel isolated or impoverished. Why should he? Standing in the heart of his nation, he saw countless questions waiting to be answered. It was a landscape filled with opportunities.

• • •

As I have written elsewhere, stereotyped images of poorly equipped STEM programs are increasingly outdated. Many tribal colleges now have facilities that match or exceed the resources of larger liberal arts colleges. Much of Native Science Report’s coverage over the past year has focused on the development of strong and well-equipped science programs.

But I am not, right now, thinking about buildings and laboratories. Instead, Clifford’s comments are a reminder that the tribal colleges’ greater strength their sense of place. Founded by tribes and located (in most cases) on Native lands, these colleges do more than educate Native students; they also strengthen tribal nations. This nation-building mandate makes tribal colleges unique, and irreplaceable.

Working and teaching in a tribal college context is not easy, and faculty who want a frictionless academic experience will struggle. “We’re all working with traumatized communities at some level,” said Kerry Hartman, who first came to the Fort Berthold Reservation of North Dakota in the 1970s as a VISTA volunteer and now teaches environmental science and serves as academic dean at Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College. Those familiar with communities served by the colleges don’t need to be reminded of all the barriers their students face: poverty, substance abuse, a legacy of low academic expectations, and a sense of limited horizons.

Working in reservations can be difficult, especially for faculty who are not Native. But the things that make teaching hard also give the work meaning. Tribal colleges and their STEM faculty are not simply providing degrees; they are confronting this trauma by making education accessible, and meaningful. “Students want to learn about the old ways,” Hartman said. In other words, they want to learn who they are, and recover a sense of purpose and pride, which is essential for academic success.

This connection to place and people also shapes the kind of research the colleges and their faculty pursue. Tribal lands have been aggressively exploited and badly treated by industries and the federal government. As we have recently documented, many Native nations are suffering from the effects of uranium mining, coal extraction, and fracking. In some cases, tribal colleges are the only institutions to engage in sustained investigation of the environmental and health repercussions. Likewise, college faculty and their students are also working to revitalize endangered languages and document traditional environmental knowledge.

• • •

The United States is in the midst of a high stakes debate about the value and purpose of higher education. Across the country, students are increasingly encouraged to view college as simply a path to employment. They are told to focus on degrees that offer the best financial “return on investment.” Meanwhile, higher education’s larger social mandate is falling by the wayside. Even large state university campuses are systematically dismantling the liberal arts, compelled by politicians unwilling to support learning that does not (in their view) advance national economic interests.

But tribal colleges, at their best, demonstrate that higher education plays many important roles in society. They know that jobs matter, but not at the expense of the greater good. Oglala Lakota College environmental science instructor Jason Tinant observed, for example, that employment-oriented training can be counterproductive if it does not consider the larger needs of the community. “A tension exists between Native communities and industry in terms of the acquisition of social capital,” he recently wrote. “While industry offers students internships and jobs, the net outcome is that the most highly skilled members of the community are taken away from the community.” Tribal colleges believe they must empower both individuals and societies.

In these ways, the work of teaching and research is not about advancing a particular discipline or even about inculcating a set of useful skills. It is also about asking questions that mingle the practical with the philosophical, and even spiritual: What is a meaningful life? What responsibility do we have toward others? Toward the earth? Toward the future? Tribal colleges and their faculty grow stronger when the search for answers shapes the acts of teaching and learning.

Paul Boyer is editor of Native Science Report