Out of necessity, tribes became leaders in the battle against Covid-19. A recent conference, hosted by Dine College, investigated what the nation can learn from their work.

By Paul Boyer

Without question, Native communities were severely affected by Covid-19. But it could have been worse. Strong and effective action by many tribes helped lower infection rates—and the lessons learned from this work can help the nation prepare for future epidemics.

That was the central message of a February 19 conference, “Emerging Infection and Tribal Communities: What We Learned From the Covid-19 Pandemic,” hosted by Dine College, a tribally controlled college located on the Navajo Nation.

Held virtually on Zoom and broadcast on Facebook, the event attracted over 500 participants from around the world. Presenters included researchers, public health experts, community activists, and cultural leaders from indigenous communities in the United States and Canada.

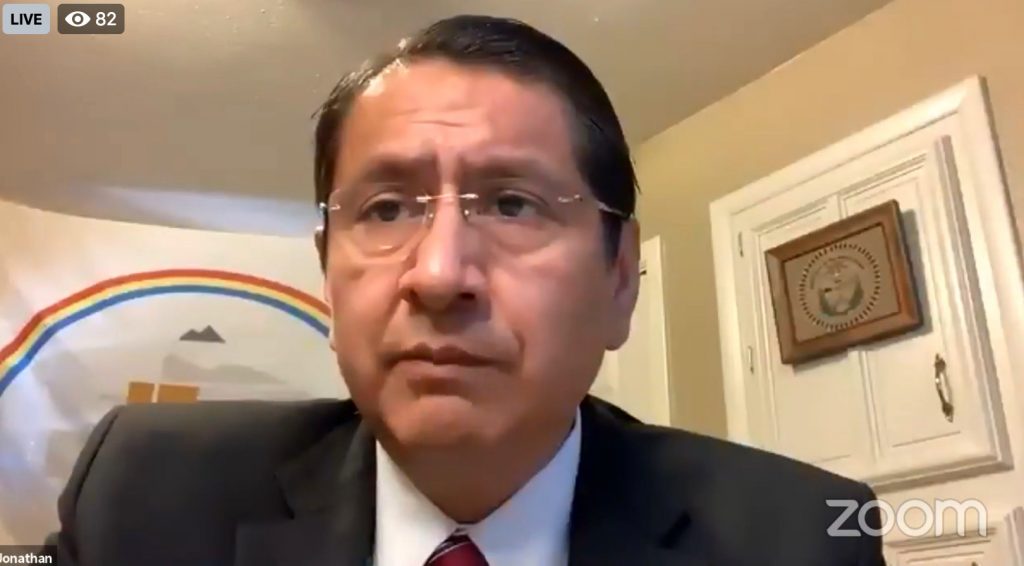

During the day-long event, speakers agreed that tribes have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. In his welcoming remarks, Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez acknowledged the price paid within his community: over 1,000 deaths to date in a tribe with approximately 170,000 members.

However, Nez said the Navajo government reacted quickly to limit transmission. Working with tribal health officials, educators, and community leaders, it declared a public health emergency, implemented mask mandates, restricted gatherings, limited travel, closed schools, and developed an aggressive public health education campaign.

Some of these measures were considered extreme at the time and Nez acknowledged that, after nearly a year, “people are getting antsy.” But he argued that the Navajo Nation avoided the “third wave” that hit other parts of the country “because of the strict protocols we put in place.”

“It could have been a lot worse,” he said, noting that infection rates are now at “an all-time low” and that Dr. Anthony Fauci, speaking at a tribal town hall, called the Navajo response “a model.”

Early in the pandemic, the tribe had one of the highest infection rates in the country, which put Navajos and their “plight” in the media spotlight for several months. “But when it comes to positive reports, not many people hear about that,” Nez said.

Several speakers pointed out these accomplishments were made despite severely limited resources within Native communities. Dr. Jill Jim, executive director of the Navajo Nation Department of Health, said the reservation, which encompasses a territory roughly equal in size to West Virginia, had only 26 ICU beds when the pandemic hit. Tribal hospitals and health care facilities were, and remain, chronically understaffed. For advanced medical care, it is often necessary to travel to distant off-reservation hospitals.

According to keynote speaker Dr. Leandris Liburd, associate director for minority health and health equity for the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), these limitations reflect a larger indictment of the nation’s treatment of minority communities.

“Covid exposed centuries of inequities in health,” she said, which are exacerbated by poverty, racism, and limited educational opportunity. This disenfranchisement also fosters suspicion of health care and public health experts, which is a particular concern as the country works to build herd immunity through vaccinations. In the coming months, Liburd said, the United States will need to promote “vaccine confidence,” which she characterized as trust in the development, efficacy, and safety of approved Covid-19 vaccines.

Speakers representing a cross section of health and advocacy organizations shared innovative community-based efforts to overcome social and economic barriers. Joining from Canada, Steve Teekens, a member of Nipissing First Nation and executive director of Na-Me-Res (Native Men’s Residence) in Toronto, described the development of a Covid-19 testing center within the homeless shelter and his organization’s close collaboration with medical experts, who also spoke about their work.

“In Canada,” he said, “we have a saying: ‘We’re all in this together.”

For Americans, this philosophy of common purpose often felt like a distant dream, especially in the early months of the pandemic when then-President Trump and many state leaders downplayed the danger, demonized health experts, and–several speakers asserted–failed to support Native communities.

Dr. Joseph Angel De Soto, a member of the Dine College STEM faculty who holds an M.D. in medicine and Ph.D. in pharmacology, said tribal public health leaders started monitoring the virus as soon as it was reported in China, “yet the federal government was deaf” and did not respond to early requests from the tribe for guidance.

“Then the bodies started piling up,” he said.

The tribe is now doing better than the rest of the country, he argued, through its own efforts. “At the end of the day, the Navajo Nation had to take care of itself,” de Soto said.

President Nez also stressed the resilience of Native communities, a trait honed through centuries of struggle. He argued that leadership shown by tribes reflects an abiding respect for life. Urging patience in the coming months, he asked, “is it worth one life” to do less than all that is humanly possible?

The conference was organized by Dine College faculty member Dr. Shazia T. Hakim, who has a background in public health research and currently teaches courses in microbiology, biology, and anatomy & physiology. Most of the conference can be viewed on demand at https://www.facebook.com/pg/DineCollege/videos

Paul Boyer is editor of Native Science Report

Published February 23, 2021

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications of new posts by email