Leech Lake Tribal College’s growing forestry program will help the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe manage a recently expanded land base.

By Melanie Lenart

After more than a century of seeing the trees on their reservation axed and even clearcut by outside loggers operating with U.S. Forest Service permits, the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe now has more say in activities on its land in Minnesota. This recent change coincides with new federal funding under the McIntire-Stennis Act for Leech Lake Tribal College’s forestry program.

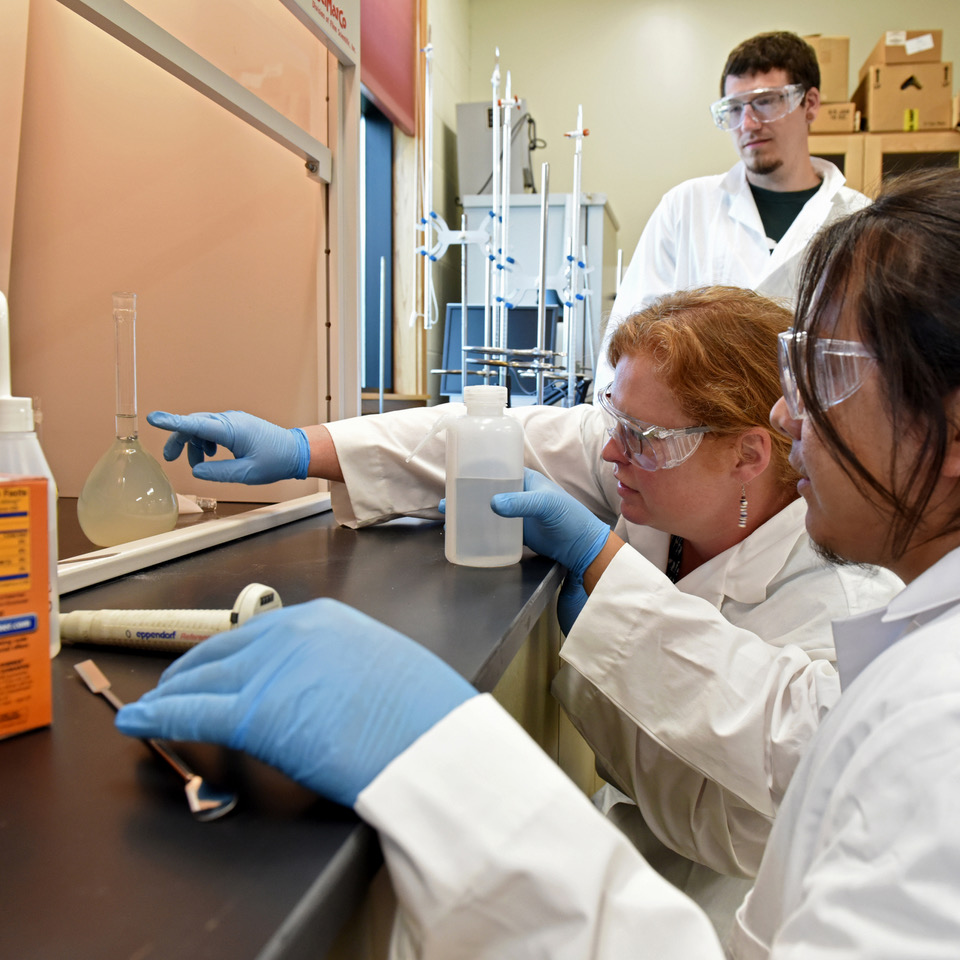

“This is all part of the larger picture of the importance of forestry for our college, for the community and for the reservation in that we need more Native scientists to manage Native lands,” explained Melinda Neville, chair of the college’s Department of Natural Sciences and Technology. “So by being part of the McIntire-Stennis program, not only is there money involved but there is increased recognition as a center of forestry that opens up more collaborations for us.”

Currently, the college’s forestry program prepares students for work as forestry technicians. With increased funding, Neville is looking forward to expanding the curriculum, increasing opportunities for research related to climate change, and building partnerships with the band’s Department of Resource Management, the Nature Conservancy, Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College, and the University of Minnesota, among others.

Thanks to a 2018 amendment to the McIntire-Stennis Act, tribal colleges became potentially eligible for this designated funding via the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. As NIFA National Program Leader Erin Riley explained in a mid-March phone call, Leech Lake Tribal College and Salish Kootenai College in Montana are the only two tribal colleges currently eligible because their forestry programs are certified.

“If more schools aligned their programs in forestry, they could get grants,” Riley added.

The funding started to kick in this year, Neville said, and the $100,000 allotted for the proposal she submitted allowed the college to hire a faculty member this month. It also reduces the need for constant grant-writing to secure piecemeal funding for a variety of collaborative research projects in the pine, birch and, more recently, aspen forests on tribal lands in Minnesota. “One of the exciting things about being included in the McIntire-Stennis forestry program is it will really allow us to increase our capacity to serve students to serve our community,” Neville said.

Even as their tribal college qualifies for the ongoing McIntire-Stennis program, the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe is benefitting from recent congressional action that returned thousands of acres of forested land to the tribe in December.

In a statement on behalf of the tribal council and the Leech Lake community, Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Chairman Faron Jackson, Sr., thanked Minnesota Sen. Tina Smith for introducing the Leech Lake Restoration Act—which passed unanimously in the Senate in late 2020—and Rep. Betty McCollum for helping to secure its passage in the House.

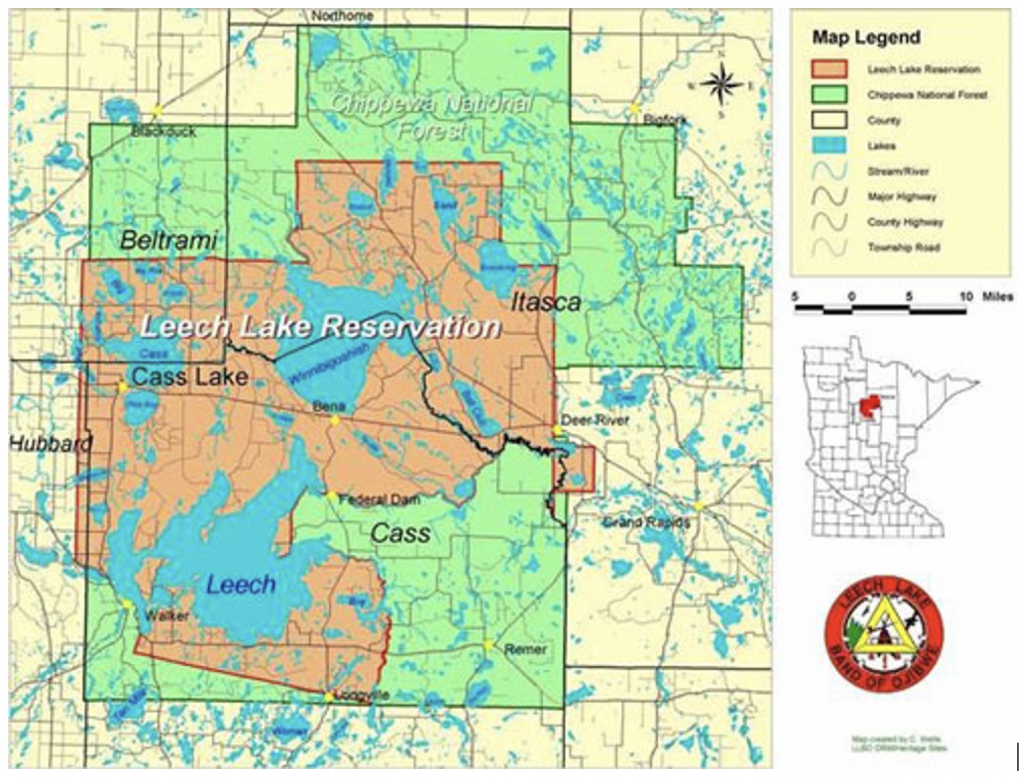

“Our reservation was established through a series of treaties and executive orders from 1855 to 1874, which promised that it would serve as our permanent homeland,” Jackson stated. “The United States violated these solemn promises repeatedly, reducing our trust lands to 5 percent of our initial Reservation. Additional lands were illegally transferred out of trust in the 1940s and 50s. The Leech Lake Restoration Act focuses on these illegal transfers by restoring 11,760 acres of our homelands to tribal trust status.”

The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe deals with an unusual situation, in that more than 90 percent of the land designated for their reservation was handed over to the U.S. Forest Service in 1902. The so-called Chippewa National Forest, as it was later dubbed for the name many used to describe the Ojibwe, includes the headwaters of the Mississippi River. In fact, the river’s name comes from the Anishinaabemowin language spoken by the Ojibwe.

In its own post announcing the December 2020 transfer of the land back to the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe—a tiny fraction of the roughly 670,000 acres comprising Chippewa National Forest—the Forest Service expressed a willingness to consider other proposals for transferring parcels back to the Band.

The new approach is a welcome change. In the past, the Forest Service overrode tribal concerns to permit the logging of extensive tracts of forest, including the old-growth jack pines that had deep roots in the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe’s culture. According to a 1942 USFS publication, the Forest Service also allowed the construction of 150 summer homes for recreational use by non-tribal members, and continues to allow hunting, fishing, four-wheeling and blueberry picking in the tribal lands that overlap with the national forest.

In a 2016 letter to the Forest Service, the band’s tribal council chairwoman explained how sharing the land base has created a relationship “checkered with injustices towards my people.”

“The Chippewa National Forest is one of the most commercialized forests in the nation, and has one of the highest percentage of cutting in relation to the allowable harvest, and one of a limited number that has no wilderness area,” wrote then-Chairwoman Carri Jones in the April 14 letter to then-USFS Chief Tom Tidwell. “All of these factors are contributing to the degradation of our natural resources and has impacted the ability of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe to practice the subsistence lifestyle which has sustained my people for generations.”

That letter launched a conversation that led to a 2018 memorandum of understanding between the Forest Service and the Band outlining a shared decision-making process designed to “give voice to the Band’s desired land management objectives.” As the memorandum states:

“This process will allow the Forest Service to benefit from knowledge offered by the Band including, among other things, Tribal Desired Vegetation Conditions, the impacts of historic trauma that may be caused by resource management, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Traditional Cultural Properties, the relationship between cultural integrity and resource management, and other special cultural or resource expertise of the Band.”

Leech Lake Tribal College’s forestry program is known as Gikenimindwaa Mitigoog, which translates as “Getting to Know the Trees.”

Both the chairwoman and the Forest Service representatives mentioned the importance of taking climate change into consideration when considering forest management. That’s something that members of the Leech Lake Band also discussed, along with the concept of restoring conditions to support culturally important plants and animals, during listening sessions held in 2017.

In a presentation called Climate Change in Leech Lake, Band member Elaine Fleming describes her concern about how past forest management along with a changing climate have taken a severe toll on the wild rice, wildlife and blueberries that have allowed the tribal members to sustain themselves and their culture.

“When they cut down these trees, what they also cut down was they destroyed that relationship that the blueberries had with the jack pine trees, those old grandfather trees,” Fleming said. “So when they cut down the jack pine and those other trees, the blueberries went away too.”

Fleming, who said the universe knows her by a name that translates as One Thunderbird Woman with the Loon Clan of the Leech Lake Nation, went on to praise the newfound collaboration between the Forest Service and the band’s own forest managers–the LLBO Department of Resource Management. The two agencies worked together after a treefall event at Cass Lake to leave some of the dead wood on the ground. With the improved conditions, she said, the blueberries are coming back.

As she spoke for one of the videos featured in the presentation, Fleming’s grandson came back to report he had spotted some blueberries near the site where she was speaking, in the regrowth from a major blowdown in 2012.

Leech Lake Tribal College’s Neville is also working with the Band’s Department of Resource Management on a research project known in the Anishinaabemowin language as Miinan miinawaa Ishkode, which involves blueberry shrub restoration. She considers her work preparing students to serve as scientists and land managers even more essential in the context of the ongoing changes to give the Band more oversight of the forests on their designated reservation.

“I think the broader goal is to increase the management and care of the landscape up here by Native American people,” Neville said. “The Forest Service recognizes the trust obligation and is working toward fixing it. This is the context for which it’s so important that we can expand our programming to help meet the need for Native scientists.”

Melanie Lenart is a regular contributor to Native Science Report.

Published March 24, 2021

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications of new posts by email