Federal funding to tribal colleges for agriculture-related programs will grow, but not as much as hoped, according to speakers at the recently concluded First Americans Land-Grant Consortium conference.

By Melanie Lenart

Federal funding for tribal colleges and their Extension programs is on target to increase—but not as much as envisioned before the scaling back of President Biden’s infrastructure plan. Other changes at the federal level also are on track to improve equity for tribes and their colleges, based on information presented in late October during the annual conference of the First Americans Land-Grant Consortium, known as FALCON.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture program—NIFA, the National Institute of Food and Agriculture—that serves 35 tribal colleges and universities banding together as FALCON seems to be stabilizing, with a new director in place who seeks ongoing input from tribes. Similarly, the group heard from the new director of the USDA Office of Tribal Relations about goals to improve equity among Extension providers and to better “indigenize” the agency. Already, some tribes are benefiting from competitive USDA funding via programs that had previously excluded them.

Future federal funding for tribal colleges likely won’t be as generous as previously hoped due to the Biden administration’s inability to gain sufficient support in Congress for its $3.5 trillion Build Back Better proposal.

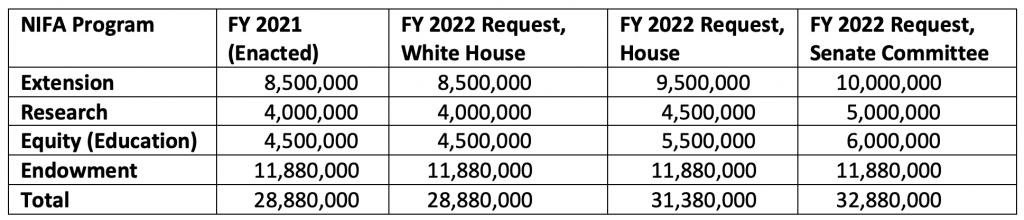

Congress is now considering a proposal involving about half that amount, but it has yet to pass. However, federal funding for several key programs serving tribal colleges is expected to increase slightly from previous years, noted Carrie Billy, the longtime president and CEO of AIHEC, the American Indian Higher Education Consortium. “There’s an increase in Extension (programs)—they’re kind of small, but they’re going in the right direction so that’s positive,” Billy reported, referring to the NIFA-administered Extension funding that supports the tribal colleges and universities.

‘Going in the right direction’

Billy expressed disappointment that the Biden administration had proposed level funding in Fiscal Year 2022 for all tribal college programs except for the community facilities program.

“That was not the case for in the Department of Education, or Interior,” she said. “That was very shocking to us. That must have been done before they got woke, you know, and heard the word inequity.”

Fortunately, she said, the House did propose increases in its completed appropriations bill, and so did the Senate budget committee for the legislation to be presented to U.S. senators. If the Senate numbers make it into the final appropriations bill due Dec. 3, funding for these programs would total about 14 percent higher than Fiscal Year 2021.

“Hopefully these Senate numbers will stick. But it’s exciting to see increases after so many years of staying level,” she told the more than 100 people participating in FALCON’s conference by Zoom. “So that’s some portion of a win.”

Still, the Build Back Better bill has so far been pared down from $3.5 trillion to about $1.75 trillion, as of Nov. 1. She noted funding had been tossed out that could have provided free tuition to community colleges, including many tribal colleges. Also in question is $40 million that had been proposed in the original Build Back Better plan for extension activities relating to tribal colleges. If it does stay, AIHEC is seeking to ensure the money goes to tribal colleges, as the language is vague.

Pell grant funding, which helps fund education and related expenses for about 80 percent of tribal college students, is also expected to increase by $500. With the $400 increase in the 2021 year, this would bring it to an annual cap of $7,300, she said.

The National Science Foundation’s Tribal Colleges and Universities Program funding could increase by 27 percent, from $16.5 million to $21 million, she noted.

Tribal colleges also gained about $800 million from three sets of federal relief funds enacted since 2020 to assist during the Covid-19 pandemic, Billy said. Many colleges used these funds to decrease or eliminate tuition for students, which boosted enrollment, or to improve internet access as colleges shifted to online teaching.

AIHEC is now working on efforts to push back pending deadlines for the use of relief funds, to make funds usable for building improvement rather than just for buying new teaching trailers, and to increase broadband internet access in the rural areas where many tribal colleges reside, Billy said.

“Going into the pandemic, when virtually every college or university in this country shut down, tribal colleges collectively and on average had the slowest internet access at the highest cost, using the oldest equipment of any group of institutions in this country,” she said. “That situation is getting better due to some Covid Relief funding, but still it remains a tremendous challenge and, we think, a tremendous responsibility for this federal government to help address those issues.”

AIHEC recommends a dedicated annual cyber infrastructure fund at USDA in rural development to help sustain the internet access that is necessary to serve students on largely rural reservations, and also to support faculty and student research at tribal colleges.

Billy also encouraged FALCON participants to apply for positions on the new Equity Council that USDA is pulling together. The deadline for nominating members is November 30. That’s another way the USDA is seeking to examine and, ideally, correct long-standing inequities in the nation’s agriculture program.

Funding disparities create inequity

“From our perspective, the inequity is the funding disparity,” Billy said near the end of her session. She said that the 35 tribal colleges and universities receive only about 2 percent of U.S. funding for the Land-Grant institutions that arrives from NIFA as Extension funding. The 19 historically Black colleges and universities receive about 16 percent of funding, while the 59 state-based Land-Grant colleges receive 82 percent of funding.

“It actually takes years of funding to dig us out of the position we’re in, so there needs to be significant increases in ag funding,” Billy said. “So that’s a huge inequity, especially when you consider that a lot of the land that created the Land Grant system was tribal land.”

The land grant system first came into effect in 1862 as part of the Morrill Act, with state-supported colleges using land or income from the sale or rental of land that had belonged to tribes to support the development of their institutions. Land grant colleges and universities were given a particular mandate to conduct research and outreach designed to promote farming and other land-based endeavors.

The arrangement has come under fire in recent years, and colleges have begun to acknowledge the debt owed to the indigenous peoples who populated the land now known as the United States.

Righting wrongs will take time

Heather Dawn Thompson, director of the USDA’s Office of Tribal Relations, also mentioned inequities during her keynote presentation for FALCON. She acknowledged the barriers in equity included the disproportionate amount of funding between the three different types of colleges in the Land Grant system.

“That’s a long-term turn shift—that’s a big boat to turn,” Thompson said. “But I want to acknowledge that we’ve heard that and we’re thinking it through.” Thompson, a member of Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe who received a law degree from Harvard, noted that she planned to participate in monthly talks with tribal citizens that NIFA has organized.

In addition, the Biden administration has reinstated the annual gathering with tribal leaders originally offered by the Obama administration, this time using the word “summit” to describe the meeting in acknowledgement that tribes are sovereign nations. The annual White House Tribal Nations Summit will be held virtually on November 15 and 16.

Thompson also called attention to differences in staffing for Extension programs serving Indian Country compared to those serving the rest of the country. While almost every US county has at least one Extension office, often staffed with multiple employees who receive formula-funding that renews automatically, few offices serve Indian reservations.

The National Congress of American Indians passed a resolution in 2010 calling for adding 60 Extension offices to serve tribes, noting that at the time, only 29 full-time employees served as “extension faculty dedicated solely to Indian reservation extension education.” Originally, 90 formula-funded employees serving tribes were envisioned for the Federally Recognized Tribes Extension Program, known as FRTEP (pronounced “fur-tep”).

The situation remains much the same a decade after that resolution. Instead of receiving formula funding that allows for greater program continuity, colleges must compete for grants every four years from a $3.2 million pool of money that represents little more than 1 percent of the $300 million granted to the state-based Extension programs.

FRTEP might reach $3.5 million for the coming year, based on the Senate committee’s proposal for the appropriations bill, Billy indicated. Still, like the Extension programs distributed to tribal colleges by NIFA, FRTEP administrators must reapply for grant funding in a competitive process that only recently opened up to tribes and tribal colleges.

Tribal colleges receive dedicated (Endowment) funds based on student count, but the other programs—for outreach (Extension), education (Equity) and research—all require grant applications every four years. Tribal college administrators are gearing up for submittals this spring. Funding can be lost for missed deadlines.

NIFA recovering from downsizing

Erin Riley, the NIFA administrator who directs tribal programs, works closely with tribal colleges to keep money flowing properly. She received a hearty round of applause at the 2019 in-person FALCON conference for her decision to stick with the NIFA program after the Trump administration moved the agency from Washington, DC, to Kansas City, Missouri. In the wake of the move, the agency lost its director and roughly three out of every four workers, leaving a skeleton crew of 80 employees working overtime to distribute the roughly $1.6 billion in program funding it administers.

At this year’s virtual FALCON conference, Riley said she was delighted to introduce not only an assistant who has been working with her for a year—cause for celebration given the high turnover of her previous assistants—but the new director of NIFA, Dr. Carrie Castille, who started in January.

Castille, a former professor at Louisiana’s land-grant college who joined USDA in 2017 to focus on the state’s rural development and regional agricultural issues, framed the agency’s recent move in a positive context.

“We’ve had an opportunity to rebuild our organization, and we want to make sure we’re doing it right,” said Dr. Carrie Castille.

Castille said she was working closely with Riley to view NIFA programs as seen by tribal constituents. She also launched monthly meetings with tribal members to learn more about how NIFA programs could better serve Indian Country. Interested people can contact Erin Riley for the link to the Zoom calls, which will be held at 1 p.m. Central time on the first Tuesday of every month.

Tribal colleges can compete for more funding

Some NIFA programs recently expanded to include participation by tribes, and others are on the horizon to do so—including FRTEP. Tribes will be able to submit grants for the $3 million to $3.5 million of expected FRTEP funding when the call for proposals occurs in 2022. (The 2021 date reported earlier was pushed back due to the pandemic.)

NIFA Director Castille pointed to an Agriculture and Food Research Initiative grant project as a laudable collaboration among minority-serving colleges. The College of Menominee Nation, a recipient of an AFRI grant, will work closely with an historically Black college, Central State University in Ohio, on the $4 million project to pair hemp production with aquaculture to improve sustainability and food sovereignty.

The project will involve feeding hemp grain to trout and other fish raised in aquaculture systems, starting with a pilot program at the college’s campus in Keshena, Wisconsin, and expanding to provide potential entrepreneurs throughout the Menominee Nation and beyond with financial start-up and training support.

The AFRI project also involves independent research at the tribal college. According to the proposal, project directors envision developing “a pipeline of Black and Indigenous and lay workforce with the appropriate technical and professional skills to fulfill employment needs in STEM, nutrition, water resource management, and sustainable agriculture.”

A $10 million AFRI project led by Oregon State University also involves expanding the hemp market, including among tribes. The project aims to “promote effective partnerships for creating new economic development opportunities centered on building a sustainable hemp-based industry” in the non-coastal areas of Washington, Oregon, Nevada and California, where hemp could be worked into rotations of small grains, alfalfa and potatoes. The proposal notes that the targeted areas fall into a semi-arid zone generally east of the Pacific Northwest maritime areas used to cultivate marijuana varieties of hemp.

So far, four tribal councils have agreed to participate in the project, according to the proposal, and many other tribes are pursuing hemp business ventures as well. The project calls for training its workers in communication and consultation skills to ensure “culturally responsive engagement with tribal communities in the region.” It also involves providing internships to high school and college students.

Two tribal colleges also started receiving money from another NIFA program that provides dedicated funding for colleges with certified forestry programs, based on 2018 amendments to the McIntire-Stennis Act. Leech Lake Tribal College and Salish Kootenai College became eligible for this dedicated funding of about $100,000 a year for their programs. SKC ran a training workshop during the FALCON conference to help other interested tribal colleges tap into this money.

Efforts to ‘indigenize’ USDA

Thompson noted that the recently appointed USDA director, Thomas Vilsack, had held the same position during the Obama-Biden administration. Having Vilsack back at the helm “makes things so much more productive” because he already knows the ropes, she said.

“As Erin (Riley) said, it really makes a difference who has these jobs,” Thompson said. Riley had made the comment in the context of introducing both Castille and Thompson, lauding them for their willingness to re-examine existing inequities.

Thompson, whose experience includes having taught federal Indian law at United Tribes Technical College, gave credit to Riley for helping her and others rethink the operations of the USDA and NIFA from an indigenous perspective, gleaned from her own work with tribes and with managing NIFA programs serving them.

Thompson listed some of the issues on the table as the agency worked to “indigenize” the USDA. They include not only the research the agency finances and carries out but also its fire-fighting policy, decisions about which foods are subsidized and which are used in commodity programs, and even the seed bank policy.

For instance, a “handful of tribes” are being allowed to purchase their own foods for commodity programs rather than go through federal procurement process, she said. The process is challenging for small-scale farms for several reasons, such as the federal government’s need to purchase large amounts of food, often at times that don’t reflect the natural growing season.

The USDA is also considering whether to establish a separate seed bank for tribes, as any varieties put into the USDA seedbank become available for anyone to use and potentially modify.

Thompson promised a “historic” announcement will emerge from the upcoming White House Tribal Nations Summit, which will be held on Nov. 15 and 16. The date was pushed back a week from the original plans announced in April. Potential participants now have until Nov. 5 to register for the summit, which will occur virtually this year.

• • •

Melanie Lenart is a regular contributor to Native Science Report.

Story published November 2, 2021.

• • •

Enjoyed this story? Enter your email to receive notifications.